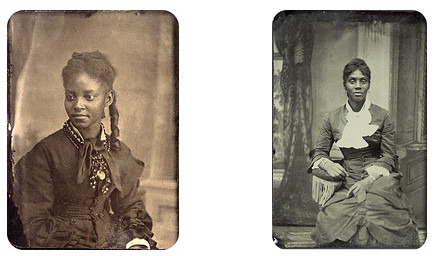

detail from untitled photo by joseph a. horne, 1940s

This photo was taken by Joseph Anthony Horne during the 1940s as he worked for the Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information. As highlighted in a previous chapter of Interludes, he like many other photographers had been sent out across the country, under the direction of Roy Stryker, to capture the American experience. One of the areas that Horne captured on film was southeast Washington, D.C., an area not far from where his family lived and an area that was predominantly African American. The photos he took in that community were notable, for me, in part because there was no characterization or stereotyping. He simply photographed in a straightforward manner people living their daily lives. He, like many of the FSA photographers, was very good at that. Otherwise in commercial media, unless it was an African-American specific publication, there was either no representation of “colored” people or it was often a mimicry. Out of all the photos that Horne took in this community, I was especially struck by the series of photos of this little girl who had been positioned in front of the camera by a person who appeared to be her mother. No doubt she’d been placed in a best dress for the occasion. And its that dress that caught my attention.

There are people far more eloquent and scholarly than I who have written and who continue to write about how we as humans form our sense of self, our sense of self-worth, our sense of what is beautiful and our sense of how we individually fit within that definition of beauty. This little girl is lovely and thoughtful. Her face clearly reads, who are you and what are you doing? The little face affixed to her dress is also lovely. Two different expressions of beauty.

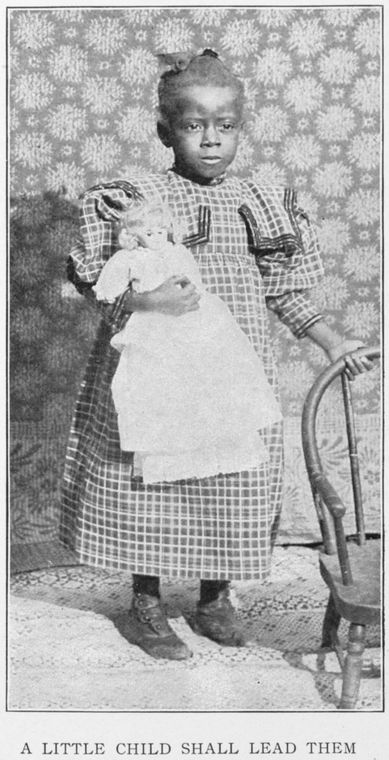

This photograph was taken in 1905 and is located in the NYPL Digital Collection. I don’t know the context in which this photograph was taken though there is that accompanying caption suggesting to me that it was in a magazine and meant as a positive image highlighting how far African Americans had come in the 40-years since slavery and that a new generation would have even more success. Too true as evidenced by the strength in that little girl’s face, and yet I am struck by the doll wrapped in her arm. Growing up in the 1970s, I too had a lovely doll around which to wrap my arms and I enjoyed combing her blonde hair and wondering why it was so hard, in fact impossible, to braid her hair the way my mother braided mine. I grew up in a far different time than these two young girls but Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, published the year I was born, certainly resonated in my teenage years. I don’t remember ever wanting blue eyes but I think I wanted blonde hair (or maybe a lion’s mane).

These musings come to the fore because of a convergence of recent events, including having the opportunity to explore the imagery being made available through digital collections, seeing images of the past that had not been made widely available before, images that today have the potential to spark positive conversations about the past, present and future.

I recently pulled together research to tell two stories of one place. One story focused on two sisters of great wealth whose lives are well-documented and whose enduring influences are often remarked upon. The second story took great effort to pull together, of a gentleman whose image and good works I could only find because of the old texts and photographs being digitized and made available online. The two sisters were white and the gentleman was black. They lived during the same time period and interacted in the same place. When I printed my drafts and shared the stories with an elder (whose age I shall not share), she listened politely to the story of the two women but she took the story of the gentleman. We had a conversation and she said, “Cynthia, all my life I have heard about these women and the people like them. I never heard about this man. You keep doing your research. Why is it important? I want people to know that we were here. To know that we were a part of this place.”

Sources

https://www.loc.gov/item/owi2001000491/PP/

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “A little child shall lead them.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1906. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-9e16-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99