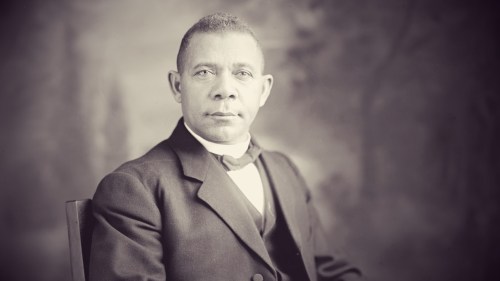

I tend to think of Emmett Jay Scott as one of those individuals upon whose shoulders giants stand. Though today he is largely unknown, during his lifetime he was a noted author, educator, activist and entrepreneur. For eighteen years he served as personal secretary to Booker T. Washington. He was Washington’s closest adviser, publicist and his friend. I knew of Emmett J. Scott because of previous research into Washington’s life and visually Scott was almost always at his side. Like Frederick Douglass, Washington was a figure well-photographed in his day. I accepted his presence but it wasn’t until I chanced upon the book, Scott’s Official History of the American Negro in the World War (1919), that I decided to learn more.

The title page states that it is a complete and authentic narration, from official sources, of the participation of American soldiers of the Negro race in the World War for democracy, profusely illustrated with official photographs. I was captured by the words “profusely illustrated.” As I perused the book online I was astounded by both the words and imagery in a publication that has been somewhat lost to time as has its author.

Booker T. Washington

Born in February 1873 in Houston, Texas, Emmett J. Scott was the child of ex-slaves. He attended Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, then worked a series of jobs before employment at a small Houston newspaper. He would eventually co-found the first African American newspaper in Houston, The Texas Freeman, and he would work with political activists like Norris Wright Cuney. Impressed by Scott’s skills, Booker T. Washington, principal of Tuskegee Institute, hired him in 1897.

Biographers note that “He became widely recognized as the leader of what was to later be known as the “Tuskegee Machine,” the group of people close to Booker T. Washington who wielded influence over the Black press, churches, and schools in order to promote Washington’s views.“[1] Like Washington, Scott believed that uplift for blacks would come through business development, the creation of strong financial institutions and nurturing economic self-sufficiency within African American communities. He ran the National Negro Business League founded by Washington in 1900. At Washington’s side, Scott was also active in U.S. politics at home and abroad. In 1909, Scott joined the American Commission to Liberia appointed by President Taft. After Washington died in 1915, Scott co-wrote a biography about his friend and mentor with Lyman Beecher Stowe, the grandson of Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Scott in 1909 as part of the Liberian Commission

Following Washington’s death, Scott remained at Tuskegee and continued to promote Washington’s philosophy through endeavors like the National Negro Business League. As Scott and other black leaders like a young W. E. B. DuBois sought to identify future opportunities for advancement while celebrating current achievements, a storm brewed across the nation. The early 1900s was a tumultuous period. Race riots proliferated and not just in the South as highlighted in this 1900 dispatch from Columbia, South Carolina regarding a New York riot.

A 1908 Springfield, IL riot and lynching prompted ministers, both black and white, to speak directly to the incident. From a New York pulpit, the Rev. Dr. Madison C. Peter’s would remark:

Seven years before Thomas Dixon’s book would be brought to the big screen by D. W. Griffith as Birth of a Nation, Peters would go on to add, “We are reaping what we have allowed to be sown. Dixon’s novels and Tillman’s speeches have been a menace to the best interests of our republic … keeping alive the race antagonism North and South, which is setting men at one another’s throats when their hands should be clasped in brotherly love.”

Thomas Dixon Jr.

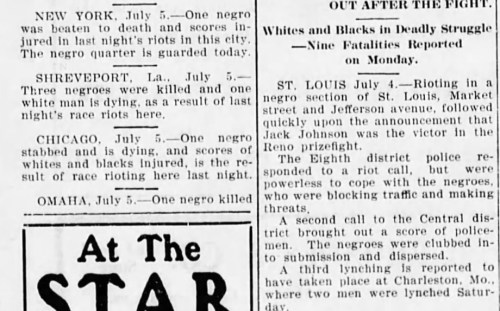

In 1910 when black fighter Jack Johnson beat white fighter James Jeffries in Reno, Nevada in a fight dubbed “the fight of the century” riots broke out across the nation.

Jack Johnson

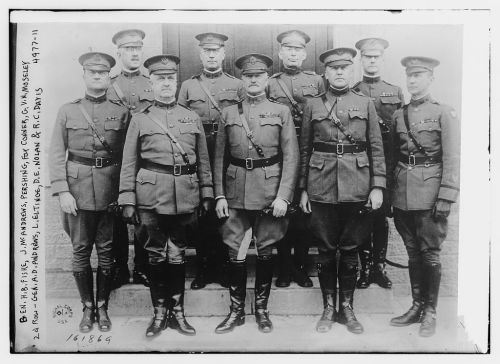

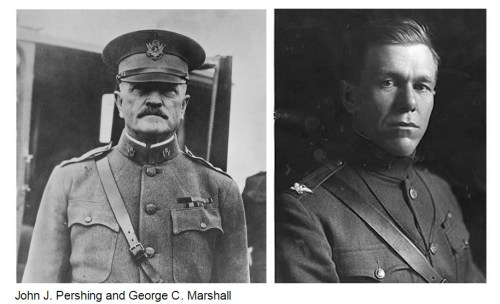

Meanwhile, by 1914, war raged in Europe. The U.S. would eventually join. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in order to make the world safe for democracy. The Selective Service Act of 1917 temporarily authorized the government to raise an army through the compulsory enlistment of Americans. The resulting American Expeditionary Force would be sent to Europe under the command of General John J. Pershing.

Pershing

When the U.S entered the war, it was unclear what the role of black soldiers was to be, assuming there was to be any role at all. After much discussion and vociferous debate it was decided all American men were needed in this Great War, and Emmett Jay Scott was to play a pivotal role in their involvement. As one biographer notes:

Robert R. Moton, President of Tuskegee and President Woodrow Wilson

“…there was considerable uneasiness as to what would be the status of the Negro in the war and quite naturally Tuskegee Institute was one of the centers which helped in adjusting these conditions. Dr. Moton, Principal, and Mr. Scott, made frequent visits to New York and Washington, and were constantly in consultation with the authorities at Washington. Out of these discussions and together with the activities of other agencies working towards the same end, the Officer’s Training Camp for Negro Officers was established at Des Moines, Iowa, and later, following a conversation between Dr. Moton and Mr. Scott, Dr. Moton interviewed President Wilson and suggested that a colored man be designated as an Assistant or Advisor in the War Department to pass upon various matters affecting the Negro soldiers who were then being inducted into the service and as the result, Mr. Scott went to Washington on October 1st, 1917, and from then until July 1st, 1919, served as Special Assistant to the Secretary of War.” [2]

draftees

Over a million African Americans responded to their draft calls and nearly three-quarters of a million served. Even as hundreds of thousands stepped forward to answer Wilson’s call, “race antagonism” continued unbridled. On July 2, 1917, a riot broke out in East St. Louis between black and white workers that left over a hundred blacks dead. In a July 4th address, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt preceded his war address to remark, “There has just occurred in a northern city a most lamentable tragedy. We who live elsewhere would do well not to be self-righteous about it, for it was produced by causes which might at any time produce just such results in any of the communities in which we individually dwell.”

Even as over one hundred indictments were being made in the St. Louis incident, an altercation took place in Houston, TX between black soldiers stationed at Camp Logan and white residents. In the end, according to one source, “Three military court-martial proceedings convicted 110 soldiers. Sixty-three received life sentences and thirteen were hung without due process. The army buried their bodies in unmarked graves.” [3]

Emerging out of the resulting nationwide protests was the question – if we are to make the world safe for democracy shouldn’t we make America safe for democracy?

soldiers from chicago arriving in france

Despite outright discrimination, verbal and physical abuses, and segragation among troops, African Americans served with distinction at every level (as they had in previous engagements like the Spanish-American War).

troop 367th known as the buffaloes

Today I know of many people, of diverse backgrounds, who have no idea of the significant role of African Americans in World War I. Why is that? In part, it is because the visuals were not produced or those that were produced — the illustrations, the paintings, the photography — were not widely distributed. They were not reproduced in the consumer publications of the period. The heroics of individuals, with rare exception, or of whole troops, with rare exception like the Harlem Hellfighters, were not retold, and certainly not in the classroom, as part of the narrative of America’s victory in the Great War.

two officers who received the croix de guerre

What was Emmett J. Scott thinking when he decided to produce his book? He tells us in the preface: “The Negro, in the great World War for Freedom and Democracy, has proved to be a notable and inspiring figure. The record and achievements of this racial group, as brave soldiers and loyal citizens, furnish one of the brightest chapters in American history. The ready response of Negro draftees to the Selective Service calls together with the numerous patriotic activities of Negroes generally, gave ample evidence of their whole-souled support and their 100 per cent Americanism. …

troop from philadelphia

It is difficult to indicate which rendered the greater service to their Country—the 400,000 or more of them who entered active military service (many of whom fearlessly and victoriously fought upon the battlefields of France) or the millions of other loyal members of this race whose useful industry in fields, factories, forests, mines, together with many other indispensable civilian activities, so vitally helped the Federal authorities in carrying the war to a successful conclusion. …

corporal fred mcintyre of the 369th

It is because of the immensely valuable contribution made by Negro soldiers, sailors, and civilians toward the winning of the great World War that this volume has been prepared—in order that there may be an authentic record, not only of the military exploits of this particular racial group of Americans, but of the diversified and valuable contributions made by them as patriotic civilians.”

369th returning home “bringing back the unique record of never having had a man captured, never losing a foot of ground or a trench, and of being nearest to the Rhine of any allied unit where the armistice was signed, and the first detachment of allied troops to reach the Rhine after the armistice.”

In The American Negro in the World War Scott produces a comprehensive account of the involvement of black Americans in World War I, those in the field and those on the home front. I believe it is an important archival record.

red cross canteen war workers in chicago

After the war Scott’s efforts with the military were both applauded and criticized. Some, like W. E. B. Du Bois, felt he should have been more vocal about the systemic racism and segregation among the troops stationed in Europe. But in wartime correspondence, just declassified in the 1980s, its clear that Scott worked hard to be a voice for the soldiers and to address injustices committed.

dr. emmet jay scott and his faithful office corps who co-operated in the performance of his duties as special assistant to the secretary of war

After the war, Scott would move on to Howard University. Outside of his university duties as Secretary Treasurer, he would continue to promote and invest in business development opportunities nationwide. He died December 12, 1957 at the age of 84.

Sources & Additional Reading

The American Negro in the World War – https://archive.org/details/scottsofficialhi00scot_0

or http://net.lib.byu.edu/~rdh7/wwi/comment/Scott/ScottTC.htm

[1] Emmett Scott, Administrator of a Dream

http://www.blackpast.org/aah/scott-emmett-j-1873-1957

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Booker_T._Washington

[2] http://afrotexan.com/AfroPress/Editors/scott_emmett.htm, a Sketch from the National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race (1919)

They Came to Fight: African Americans and the Great War

[3] http://exhibitions.nypl.org/africanaage/essay-world-war-i.html