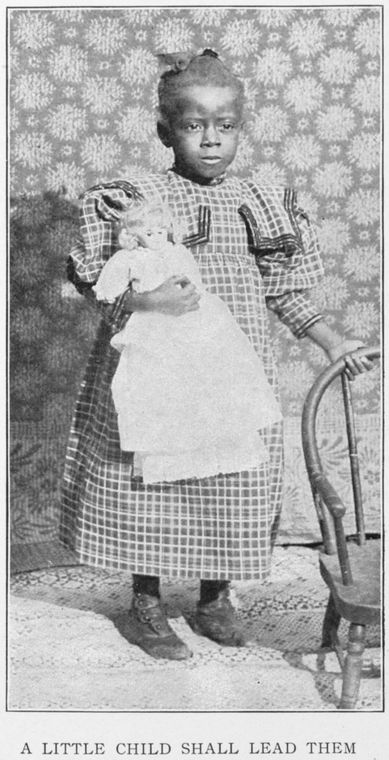

Before I began photographing the stained glass windows of St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church in Roxbury, MA, the Rector Monrelle Williams invited a longtime parishoner, Ms. Leslie Gore, to share the church history with me. An active member since a child in the 1950s, she described Sunday School classes of 300-500 children, the different guilds, the cotillions that took place, the plays produced in the lower parish hall, and much more. Finally, I asked her, if there was one thing that she wanted people outside of her congregation to know about St. Cyprian’s what would it be. With a beautiful smile, she said, “I’d want them to know that this place is home. A beautiful place to be. A place where people encompass you.” As I photographed the stained glass windows, I thought of the children she described including her own. As they raced about the church, sang in the choir, and participated in other social and cultural activities, around them they would have seen themselves and learned about their history, American history, rather uniquely.

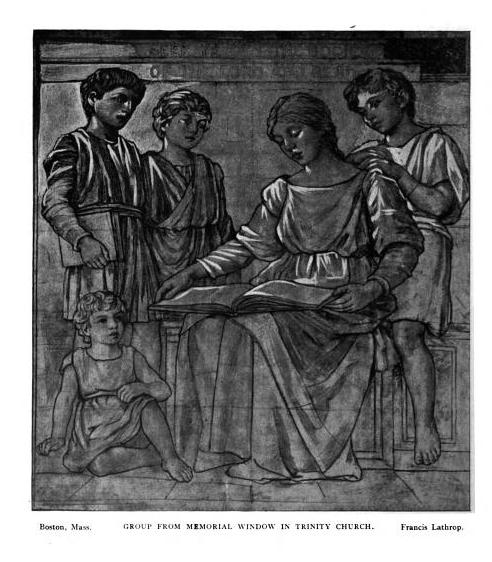

St. Cyprian’s is located at 1073 Tremont Street. While the physical structure was built between 1922 and 1924, the actual coming together of people for worship began much earlier. They were people who had emigrated to the U.S. from the former British West Indies and African Americans migrants from the southern states. Those who moved to Massachusetts primarily settled in Boston and Cambridge. It was the first decade of the 20th Century. It was a period of great change, opportunity and of racism. While many of these peoples wanted to attend existing Episcopal churches, they were rebuffed both overtly and subtly. In May 1910, a group of people decided to meet for worship in a private home. As numbers grew, they began to worship in other churches when those churches were not holding service. It was a nomadic existence, and again one where things were done – e.g. the fumigation of one church after they had left – thus spurring people, under the leadership of Reverend David Leroy Ferguson to raise the funds to buy land and build their own church. A home was created. And in that home there is lovely stained glass with traditional Christian imagery depicting figures from the bible …

… and then at some point the community of St. Cyprian’s made a decision to depart from the traditional practice of using biblical figures and to instead highlight black people, men and women, “who have made significant contributions to the liberation and empowerment of our people. … Our stained glass windows, therefore do not serve to beautify the building or to enhance its ambience, rather they serve to educate us about the outstanding contribution of men and women to the betterment of our community.” “It is my hope,” a former rector concludes in a descriptive pamphlet, “that as we celebrate their lives and deeds that we may be inspired to follow their blessed footsteps to make our community and nation a better place for all.”

Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman

Mary McLeod Bethune

Phyllis Wheatley

The images span the past into the present.

Richard Allen and James Forten

Prince Hall

A booklet titled Voices and Victors in the Struggle features the biographies of each of these people. And thanks to physical libraries and of course the internet, if you are unfamiliar with the historical significance of these folks you can choose to discover why they have been recognized in this church.

Marcus Garvey

Martin Luther King Jr and Frederick Douglass

Absalom Jones

Alexander Crumwell

The Rt. Rev. John Melville Burgess

St. Cyprian’s was built by a people rising above discrimination. Over time and deliberately, members sought to use design as a tool for empowerment and celebration of the achievements of people of color from many different backgrounds.

St. Cyprian

It was inspiring to learn of this church and its founders, and to see firsthand the beauty and history shared through its windows.

Sources & Additional Reading