Richard Lonsdale Brown was born in 1892 in Evanston, Illinois. When less than a year old, his parents moved to West Virginia. There he attended public school and then trained as a sign painter. After finishing trade school, he remained in West Virginia for five years, “and then being a journeyman sign painter I traveled through the mining districts of the state … My journeys took me almost altogether through the mountains where, when God made them, He placed scenery the equal of which, I think, cannot be found in all America.”

“It was there I believe that my love for landscape painting was awakened. When not painting signs I was doing what I could to reproduce the scenery of the mountains and valleys, the rivers and the streams on canvas.” Brown shared those words in a 1913 article that appeared in the New York Sun.

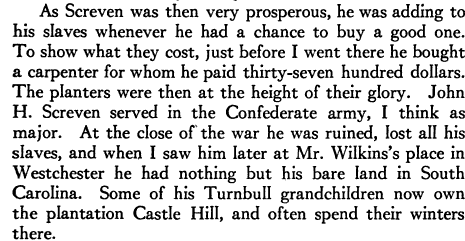

Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard, circa 1910-1920

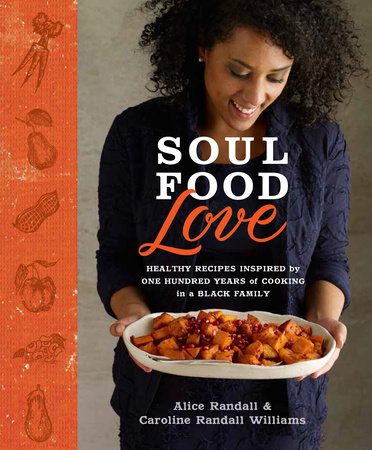

Mary White Ovington (1865-1951), co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, remembered first learning of Richard Lonsdale Brown in 1910. In her memoirs, she recounts it was during a meeting with Oswald Garrison Villard (1872-1949).”In 1910, when Mr. Villard and I were working in the newly organized NAACP, he gave me a letter from the artist George de Forest Brush, asking me if I would take up the business mentioned in it. It told of a young colored artist, Richard Brown, from Charleston, West Virginia, who had recently come to New York with some excellent sketches.”

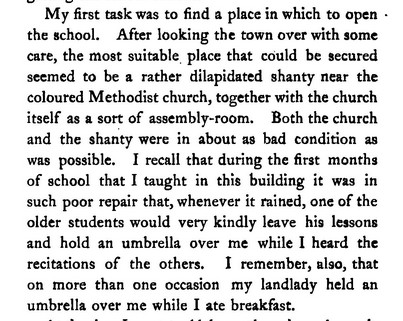

George De Forest Brush

“I called upon Mr. Brush in his picturesque studio on MacDougall Alley and saw his pictures. They were lovely things, trees and melting skies, alive in form and color. Mr. Brush was deeply impressed with them. ‘He is no more than a boy,’he said, ‘and he came into my studio, shy, discouraged. He had brought his sketches under his arm to New York, and when not in one of our great galleries was spending his time trying to sell them. No one wanted even to look at them. He was poor; he was colored. Could one have greater handicaps?’ Mr. Brush welcomed him to his studio and looked with interest and appreciation at his work. ‘Can I ever be an artist?’ Richard asked when had shown all he had. The answer was, ‘You are an artist.'”

Brown would exhibit his work in the Ovington Brothers Gallery in New York, March 18-23, 1912. It would showcase paintings done in West Virginia before he was 18 years old and in the hills of New Hampshire while under the tutelage of Mr. Brush. Mary Maclean, a writer with the New York Times wrote a profile of the young artist for the newspaper. The article appeared in March, just before the exhibit, helping to make it a great success.

It was estimated that 2,500 people attended. Twenty-six pictures were for sale and sixteen were sold including little sky sketches. The young man charmed people with his demeanor as well as the quality of his work. Collectors who reportedly purchased his work included Jacob H. Schiff, Edward Warburg, Mr. Coster, and celebrity Miss Mary Garden.

Art Critic Joseph Edgar Chamberlin quoted in the New York Age, March 1912

Maclean’s profile would also be printed in the April 1912 issue of the NAACP’s The Crisis Magazine for which Richard Lonsdale Brown produced the cover.

Cover Art by Richard Lonsdale Brown

Ovington remembered, “Crowds came and he had many purchasers. The prices for most of the pictures were high, and so Richard would paint little cloud sketches in the evening and sell them the next day. He made over a thousand dollars. We all hoped he would use it for study; I had plans for Paris but the money went where his affections dictated. He spent it on a sister, who he used to tell me, was more talented than he, in a vain attempt to cure her of what proved to be an incurable disease.”

by Richard Lonsdale Brown

White and black publications of the period described him as “the rising young artist.” Instead of Paris, Brown would study in Boston, living at the Robert Gould Shaw House. Ovington remembers him producing posters for W. E. B. Du Bois’s Pageant. He exhibited in private homes. He would eventually travel down South. Before he left, he would confide to Ovington that he could not paint as he used to. He’d begun painting landscapes but was now intrigued by figures. As he studied those figures he was discouraged at how society beat them down. He was excited by what was happening in Harlem and hoped to be a part of it. “Not that I have forgotten what I want to do most of all, ” he would tell her. “Someday, when I am the artist I hope to be, I want to return and paint those West Virginia hills.”

Mt. Monadnock, originally purchased by Jacob H. Schiff

While it is unclear if he returned to those West Virginia hills, he would not be part of what became known as the Harlem Renaissance, nor would Ovington see him again after that last encounter. In 1915, he would exhibit his work in the Washington, DC home of Mrs. Carrie W. Clifford. He died September 23, 1917. Posted in the March 1918 issue of The Crisis was the following passage: “The parents of the late Richard Lonsdale Brown write us that they are living in Muskogee, Okla, and that the young artist died at their home and under their care.”

A Bend in the Stream, originally purchased by Albert Andriesse

While it appears that the three paintings above and the 1912 Crisis cover are his only surviving work, clearly he produced many other sketches and paintings during his brief lifetime. So perhaps somewhere out there are Brown’s little cloud sketches, scenes of melting skies and his West Virginia mountains.

Sources and Additional Readings

Negro Youth Amazes Artists By His Talent, New York Times, March 1912

Richard Lonsdale Brown Biography by the Indiana Illustrators and Cartoonists

Black and White Sat Down Together: The Reminiscences of an NAACP Founder (pp. 75-76)