Posts Tagged ‘art history’

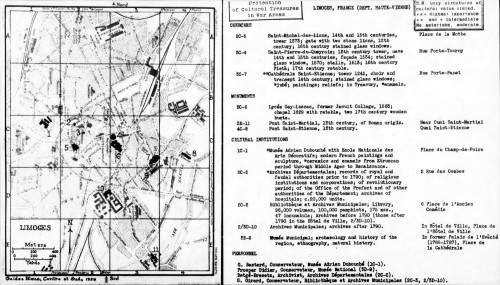

on this veterans day a revisit …

Posted in Inspiration, tagged American history, art history, history, Inspiration, Monuments Men and Women, Photography, veterans, war history on November 11, 2023| Leave a Comment »

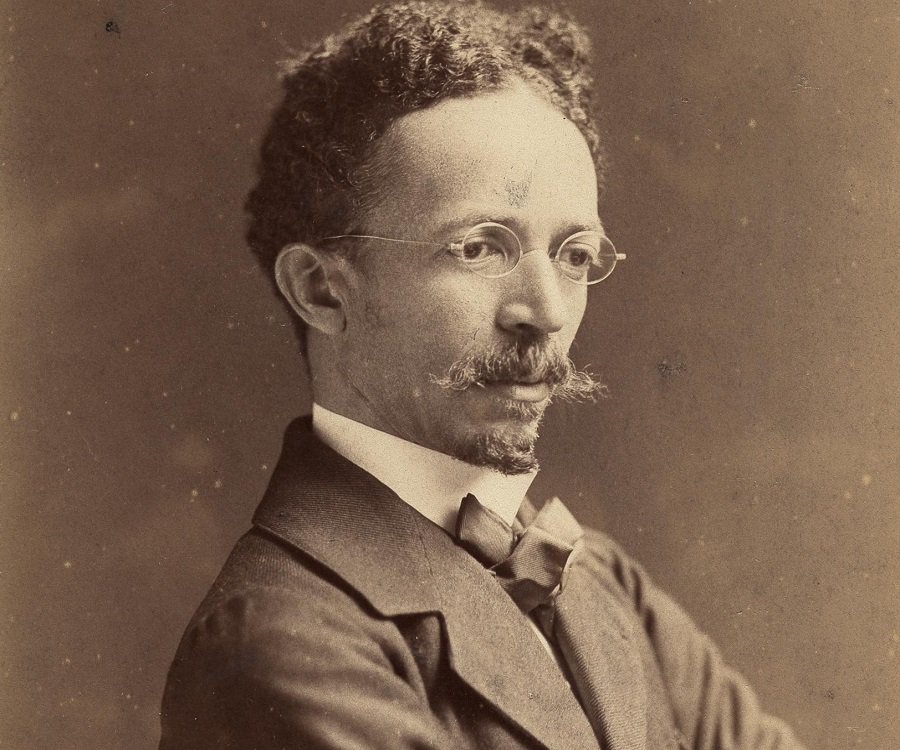

do you know … henry ossawa tanner

Posted in Inspiration, tagged American history, art, art history, beauty, emigration, faith, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Inspiration, race relations, religion, storytelling on February 9, 2017| 13 Comments »

Editorial note: This post was written in part in response to the current Presidential administration’s recent remarks this Black History Month, and its seeming lack of knowledge regarding black history in this country. It is also written to share in brief the life and work of an artist whose work I have always admired.

Henry Ossawa Tanner 1859-1937

Henry Ossawa Tanner was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1859 and grew up in Philadelphia. Tanner’s father, who happened to be a friend of Frederick Douglass, was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal church. Tanner’s mother, who had escaped slavery in Virginia via the Underground Railroad, taught private school in the home. Both staunch believers in education, they made sure their son, the eldest in a large family, was well-educated and prepared for a successful career in a conventional job.

The Tanner Family

Tanner had a slightly alternative idea. He too wanted to be successful and he wanted to be a painter. He’d known since the age of 13 after watching an artist at work in a Philadelphia park. Eventually, his father relented and he was allowed to pursue his artistic calling. In 1879 he was admitted into the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, the first African American student to attend full-time.

Biographers refer to the fact that Tanner would write little about his time at the academy, mostly focusing on what he learned from Thomas Eakins with whom he studied. Regardless, it was an important period in Tanner’s life, not only for what he learned about art but also about human nature.

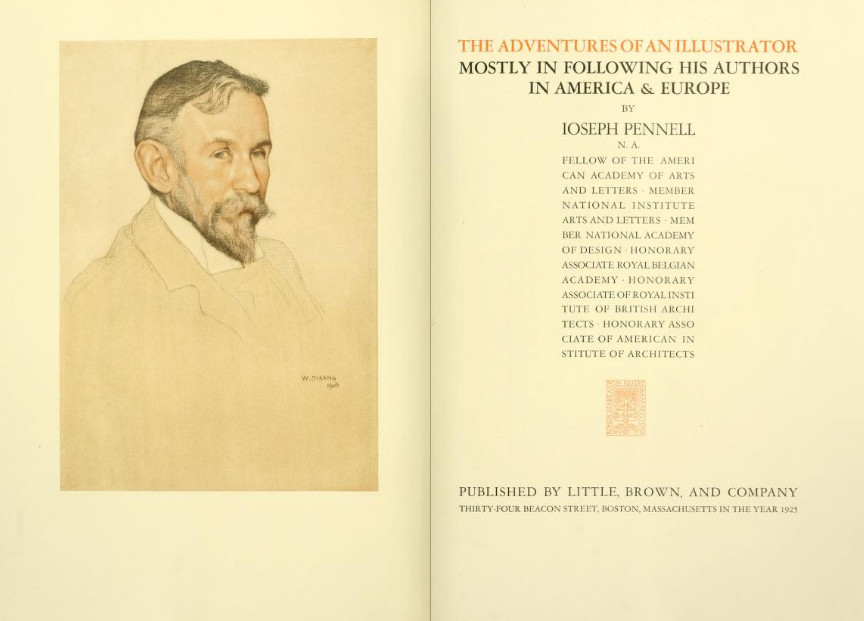

Already in attendance at the academy prior to Tanner’s arrival was student Joseph Pennell who would one day be recognized as a great American illustrator. In his 1925 memoir Pennell makes note of Tanner’s arrival at the school in a chapter titled, The Coming of the Nigger.

Ship in a Storm, 1879

“There was no dissenting voice in the academy against Tanner’s presence. He came, he was young, an octoroon, very well dressed, far better than most of us. His wool, if he had any, was cropped so short you could not see it, and he had a nice mustache. … he drew very well. He was quiet and modest, and he “painted too” it seemed “among his other accomplishments.” We were interested at first but he soon passed almost unnoticed … Little by little however we were conscious of a change. I can hardly explain, but he seemed to want things; we seemed in the way, and the feeling grew.”

Seascape – Jetty, 1876-1879

One night while out on the town with Pennell and other students, Tanner was mocked by other African Americans for being with the white students. Pennell recalls, “Then he began to assert himself and, to cut a long story short, one night his easel was carried out into the middle of Broad Street, and though not painfully crucified, he was firmly tied to it and left there. And that is my only experience of my colored brothers in a white school. Curiously there has never been a great Negro or great Jew artist in the history of the world. …”

Tanner studied at the academy through 1885. By 1889 he moved to Atlanta. He was unsuccessful in a photography business venture. During this period he made the acquaintance of Bishop Joseph Hartzell of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Hartzel and his wife became patrons, helping Tanner secure a teaching position at Clark College, encouraging him to exhibit his work and eventually funding a trip for him to Europe. In Europe, Tanner discovered an environment where he was not a “negro painter,” he was simply an American painter. In 1891, he emigrated to Paris where he would study at the Academie Julian.

The Banjo Lesson. 1893

After contracting typhoid fever, he returned briefly to the U.S. to recuperate. During this period he delivered a speech at The Chicago Congress on Africa at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition about negro artists and sculptors. In 1893 he would also complete one of his most iconic works, The Banjo Lesson. Tanner had originally sketched this scene in the late 1880s while traveling in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina.

The Thankful Poor, 1894

In two paintings, Tanner portrays the beauty and dignity of African Americans, and does so in a way that is purposefully counter to the increasingly derogatory depictions of African Americans in art, newspapers and other consumer publications. Numerous prints of these paintings were made and hung in the homes of African Americans as a source of pride and inspiration. Tanner would produce few, if any other, such paintings of African Americans. Regardless, wherever Tanner traveled in the world, he captured the vibrancy of the people he saw around him.

The Young Sabot Maker

With his religious paintings, he especially played with color and light.

Resurrection of Lazarus

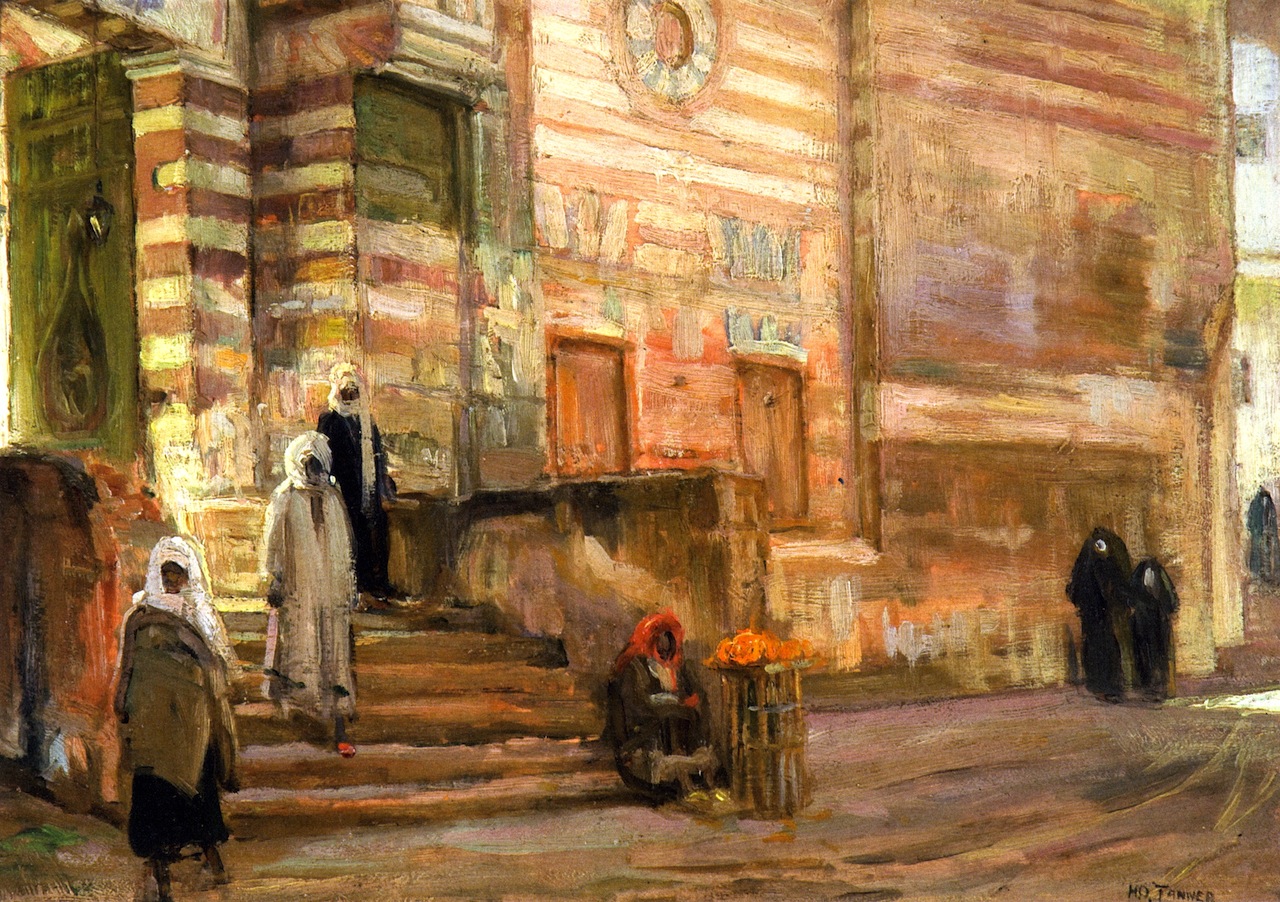

After being moved by Tanner’s Resurrection of Lazarus, department store magnate and art critic Rodman Wanamaker offered to sponsor a trip to Palestine. Tanner traveled throughout North Africa and the Near East. The journey further informed Tanner’s work with religious narrative.

Mosque in Cairo

Aside from The Banjo Lesson, Tanner is now most often remembered for the breadth and beauty of his religious themed works.

The Anunciation, 1897

Jesus Visiting Nicodemus, 1899

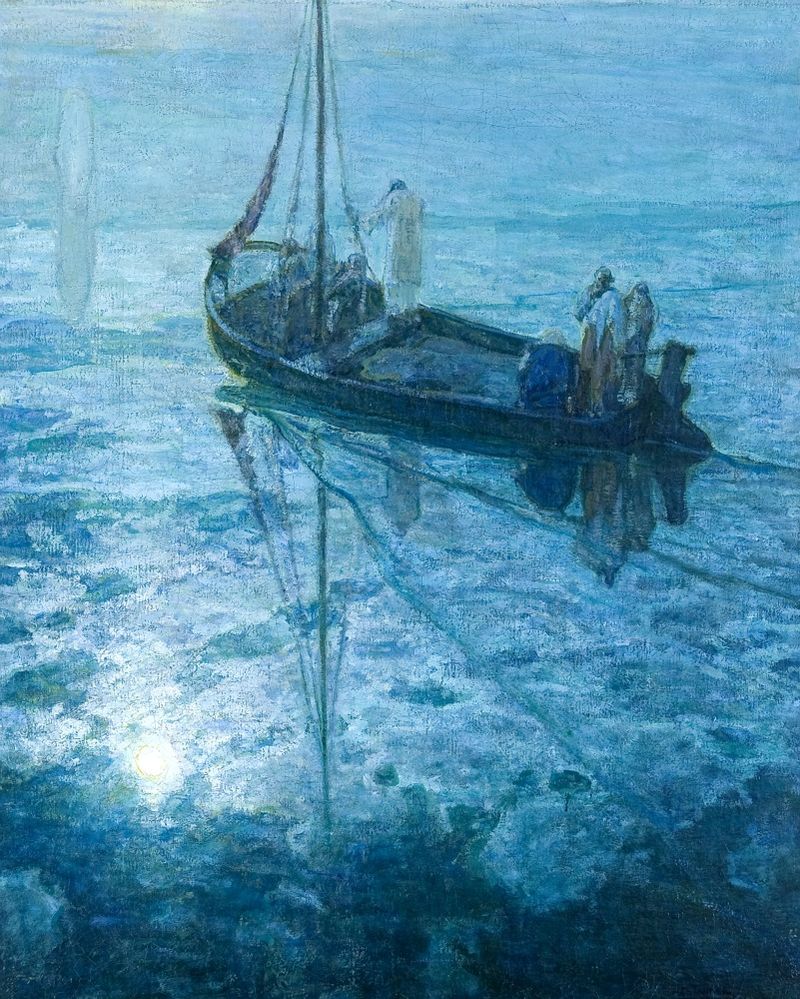

The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water, 1907

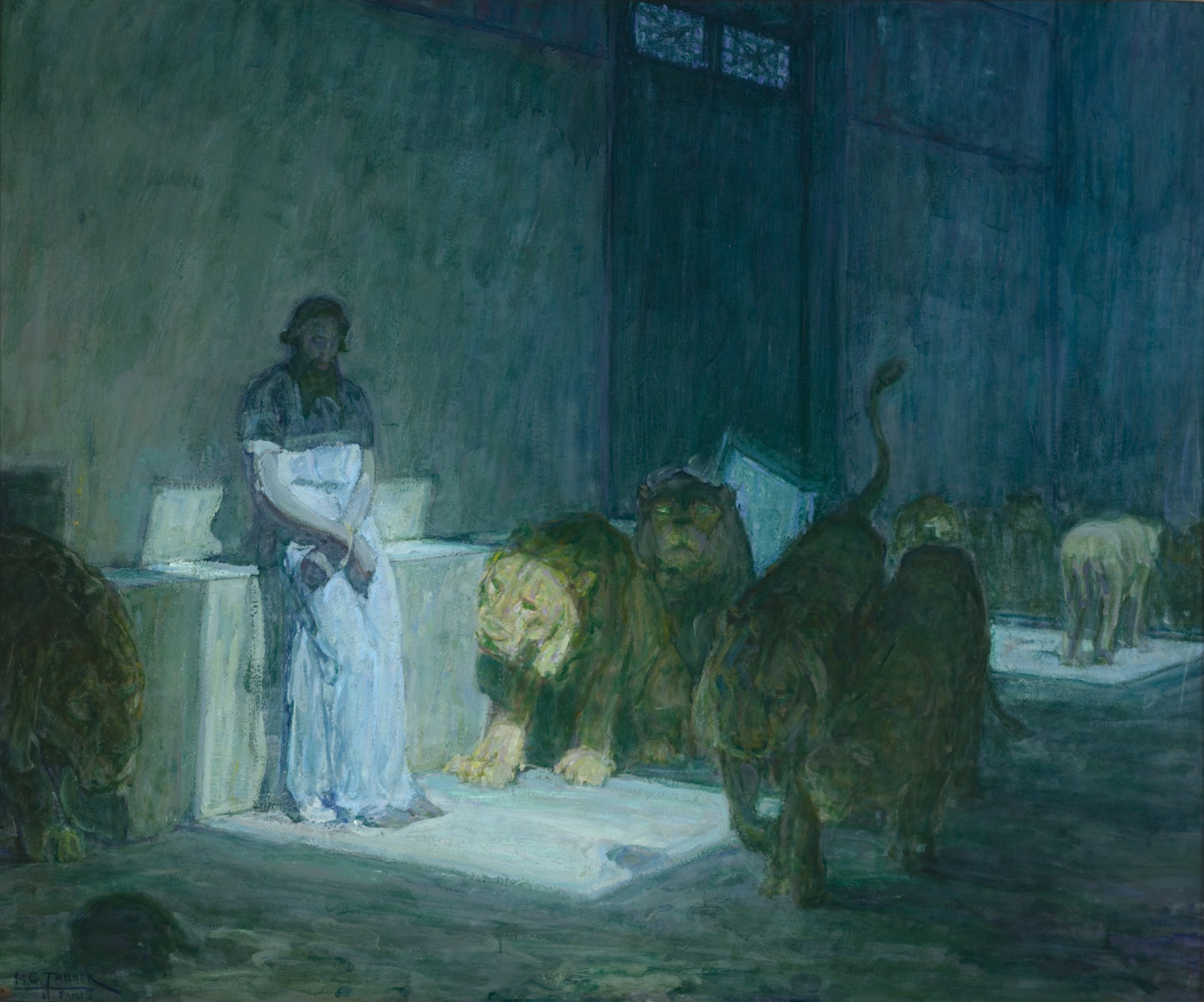

Daniel in the Lion’s Den

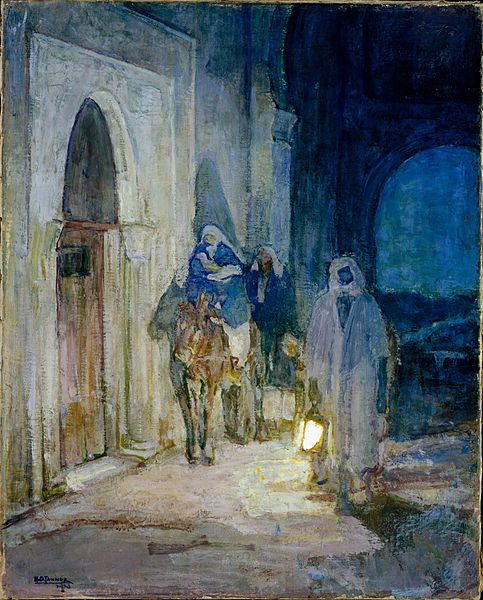

Flight into Egypt, 1923

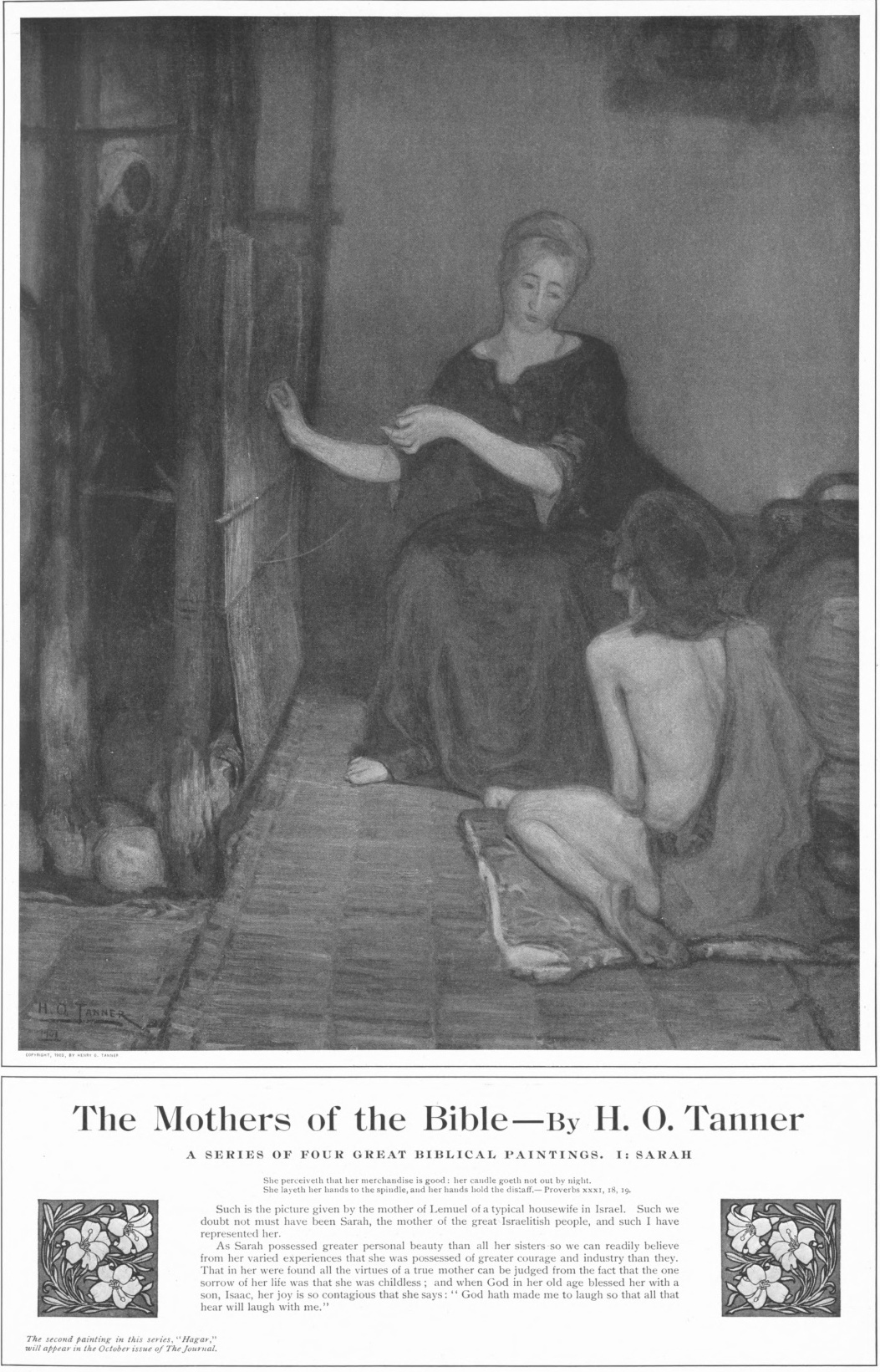

In 1899, Tanner married Swedish-American opera singer Jessie Olsson. They had one child, Jesse. Tanner continued to paint, exhibiting internationally. He expanded his list of patrons. In 1902, over the course of four months, four of his paintings – Sarah, Hagar, Rachel and Mary – were reproduced in the Ladies’ Home Journal. He became renowned though he would always struggle financially.

As World War I broke out in Europe, Tanner became depressed. He was unable to paint. Or what he painted while respected was not being purchased. He wanted to serve in some way but he was too old to enlist. He shared an idea with the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom Walter Hines Page. His idea: turn the unused fields around the base hospital in Vittel, France into a vegetable garden and organize the convalescing soldiers as a work force. Provide food. Build morale. Page reached out to his counterpart in France and soon after Tanner was attached to the American Red Cross as a Lieutenant in the Farm Services Bureau. In 1919, for his efforts, Tanner received a Foreign Service certificate signed by Woodrow Wilson.

Postwar, Tanner would resume painting and once more receive accolades for his work. In 1923 Tanner was made a chevalier of the Legion of Honour for his work as an artist. In 1927 he became the first African American to be granted full membership in the National Academy of Design in New York.

Tanner lived during one of the most contentious periods in U.S. race relations. While he chose to emigrate to France, he always considered himself an American. He was a mentor and adviser to artists of all races studying in Europe. He was vocal in print and in person in support of equal opportunity for artists of all backgrounds. On May 27, 1937, he died at his home in Paris.

Today, Tanner is most often referenced as one of the great African American painters. I suspect he would simply like to be known as a great American artist. His painting, Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City was the first work of art by an African-American artist to be added to the White House Permanent Collection. It was acquired in 1996 from Dr. Rae Alexander-Minter, grandniece of the artist.

Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City, 1886

Sources & Additional Reading

Treasures of the White House: Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City

Henry Ossawa Tanner Wikipedia Page

A Missing Question Mark: The Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner by Will Smith

http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artist/?id=4742

Khan Academy Course on Tanner’s Banjo Lesson

The Adventures of an Illustrator by Joseph Pennell

Photograph of the Extended Tanner Family, 1890

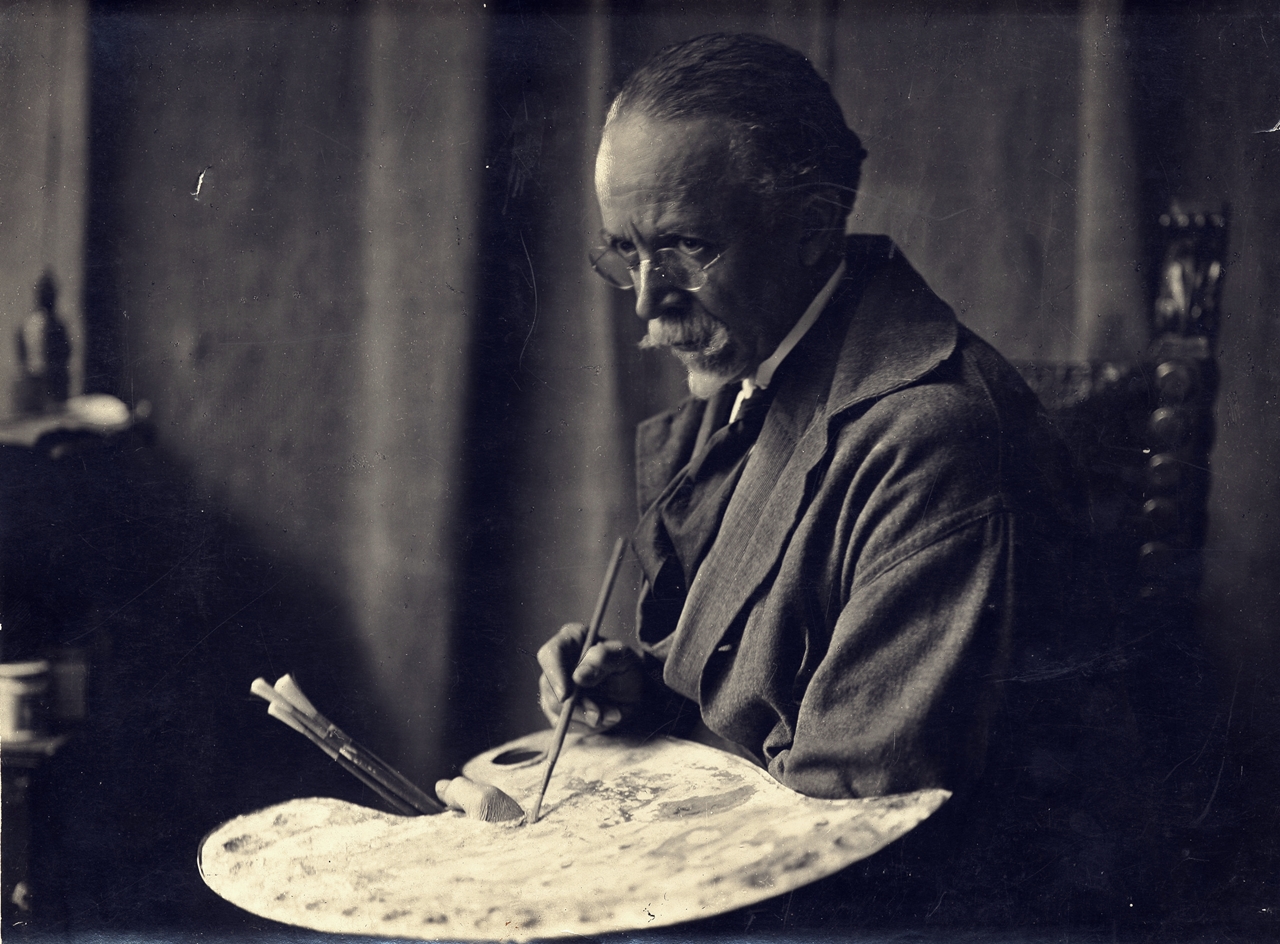

Henry Ossawa Tanner| Realist/Symbolist painter

Henry Ossawa Tanner: Race, Religion and Visual Mysticism by Kelly J. Baker

Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist by Marcia M. Mathews

so far untitled

Posted in Inspiration, tagged art, art history, beauty, Inspiration, Photography, religious art on October 31, 2016| 2 Comments »

In a church, I walked into a room to photograph a specific set of stained glass windows that were at eye level, and when I turned to walk out I happened to look up and this is what I saw hanging on the wall. I don’t yet know the name of painter or painting. That research continues, and if you have any incites please let me know. I’m not a formal student of fine arts but I can imagine that there are layers upon layers of meaning in the choice of colors, the flowers shown, etc. More information to follow in the near future I hope.

delving into the past: st. dominic and pierre bourdelle

Posted in Inspiration, tagged Antoine Bourdelle, architecture, art, art history, Auguste Rodin, creativity, illustration, Inspiration, murals, painting, Pierre Bourdelle, research, sacred architecture, St. Dominic, storytelling, war on May 23, 2016| 2 Comments »

St. Dominic’s life is on display in Stephen’s living room. Grand in its expression, it appears in a small painting on paper, only slightly larger than 2′ x 2′ unframed. It is in fact the colorful sketch for a much larger work — a mural on the wall of St. Dominic’s Priory in Washington, D.C.

Each section of the painting, and of the final mural, has meaning. The image is divided into seven parts, depicting seven scenes from Dominic’s life, from the center upper part where “God’s Hand puts halo around St. Dominic and drops into beggar’s bowl a star …” to the center lower part where “Two Angels lift the saintly pilgrim by his bleeding feet toward the stars in heaven.”

The painting was in the possession of Ludwig Joutz (1910-1998), an architect with the D.C. based firm, Thomas H. Locraft and Associates, noted for what today is often described as sacred architecture. In 1960, his company designed a new priory for St. Dominic’s Church. Construction was completed in 1962. On a lined office pad Joutz sketched the initial concept for the mural. That yellowing piece of paper remains with the painting, a painting that is signed and dated by artist Pierre Bourdelle (1901-1966).

Loutz must have treasured Bourdelle’s work. After he retired, he and his wife moved to Florida and with him he carried Bourdelle’s painting. Loutz, himself an artist, would sketch the interior of his home in Florida. In one drawing there on the wall is the same painting that Loutz’s son would eventually give to Stephen after his father’s death.

artwork by ludwig joutz

Ludwig’s son remembered his father meeting with Bourdelle as he worked on the mural but little else could he tell me and so my research began. Thankfully, there was quite a bit of information to be found online and in newspaper archives.

Born in Paris, France, Pierre Bourdelle was the son of famed sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. He studied under Auguste Rodin in whose studio his father worked from 1893-1908. During his time as Rodin’s chief assistant, his father taught the likes of Henry Matisse and Alberto Giacometti. One biographer notes that with Rodin, a young Bourdelle visited Europe’s great Cathedrals.

rodin by edward steichen, 1911

Eventually Pierre would move to the United States and set up a studio in New York. In effect, he stepped out of his father’s shadow.

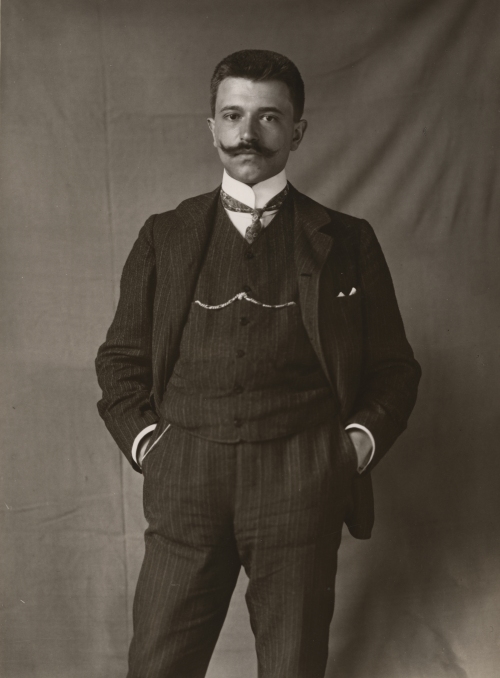

antoine bourdelle, 1925

In a 1934 interview, he expressed: “In France, a man is judged by what his father did or by his family tree. In the United States a man is judged by himself, his personality, his own work. In France, they offered me mural jobs because my father was a well-known artist. They did not even look at my work.”

pierre bourdelle, 1934

A man of diverse interests and talents, he’d traveled the world studying the art of different cultures, observing the nature of different places. Over time, based on some of the things he’d seen, he developed a new technique that set him apart as a muralist.

excerpt from 1934 article

Search online and you’ll find a wealth of information about his Art Deco paintings and sculptures from the 1930s and 1940s. His bold and vibrant work adorned the interiors of ocean liners, railway lines like the California Zephyr, and the walls of institutions like Union Terminal in Cincinnati.

jungle mural by bourdelle for cincinnati terminal

He was a versatile artist capable of working with many media. For Cincinnati’s Union Terminal, he not only created exotic jungle murals carved in linoleum, he also painted the ceilings of several rooms using an electric spray gun on canvas.

For the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair, he created murals for Food Building North No. 2. As described by a journalist covering the fair for Collier’s Magazine in 1939, “There was Pierre Bourdelle, stripped to the waist in the hot sun and covered with red plaster dust. Gobs of wet plaster, a good blank wall, tools in his hands. That’s all Bourdelle, pupil of Rodin, asks to make him happy.”

His design motif for the fair was described as low bas-relief representing Bacchantes reveling at a wine-harvest festival, mythological animals, and scenes of beverage-making in various cultures.

sunshine and rain by bourdelle 1939

larger detail of vineyard mural on food building, 1939

While not everyone appreciated his style, e.g. so many sinuous forms wrapped around each other, few could deny the provocative and captivating nature of his work.

When World War II broke out, Bourdelle felt compelled to join the war effort. He’d served in France during World War I. He’d been too young, only 15, but he’d lied about his age and was able to join an aviation unit. When his plane went down, he suffered traumatic ear injuries. A number of the biographies I found suggest that the horrors of that first war, the so-called Great War, influenced his art as no doubt did his participation in World War II. While unable to enlist because he was considered too old, he did serve in his own way, as a volunteer ambulance driver with the American Field Service at the North African and Italian fronts.

In 1945, upon his return to the U.S., Bourdelle would produce a book of images, simply titled, War. For the foreward, Stephen Galatti , the Director General of the AFS, would write, “Overseas Pierre Bourdelle saw suffering. He did his best to alleviate suffering, driving the wounded soldiers of many Allied armies. Helping staunch and bind their wounds in the field dressing stations. He knows the agony of war. He has no fear of showing war at its useless worst. He is not only a personally brave man who volunteered to go, and went, wherever the wounded were. He is an intellectually brave man, who makes no pretense at hiding the bare hideousness of warfare. … They are not pretty pictures. They show nothing but reality …”

They may not be pretty but they are horribly beautiful. And as I perused all 50+ images, viewable online here, I could not help but be fascinated by Bourdelle’s evolution as an artist …

… seeing these works done in the 1940s and then …

… being able to look at the drawing he did in the early 1960s for the St. Dominic mural.

I suspect I will never see in-person the actual St. Dominic mural. First of all, it is in a monastery chapel. Second of all, it has been covered in an attempt, I believe, to preserve it from the deterioration of time.

During the latter years of his life, Pierre Bourdelle continued to work as an artist and as a teacher. He taught at C. W. Post, part of Long Island University, as an artist-in-residence. He died in 1966 while traveling with his family in Switzerland.

Sources and Additional Reading

Bourdelle Family History – http://www.mountharmonyfarm.com/GH-P-BourdelleItems.html

SS America Unique Story of a Great Ocean Liner/Bourdelle Page – http://www.ssamerica.bplaced.net/art2-en.html

Artwork for the California Zephyr – http://calzephyr.railfan.net/artists/bourdelle.html

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Art – Murals – Food Buildings – The Vineyard (Pierre Bourdelle)” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1935 – 1945. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e8-7352-d471-e040-e00a180654d7

Collier’s, Volume 103, p. 16

Bourdelle Art for Dallas Fair Park – http://frenchsculpture.org/dallas-fair-park-1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cincinnati_Museum_Center_at_Union_Terminal

The Glass Storybook and the Great Menagerie The Art of Winold Reiss and Pierre Bourdelle – http://www.cincymuseum.org/union-terminal/art

History of Cincinnati Union Terminal – http://library.cincymuseum.org/75th-anniversary/main.swf

Bourdelle’s War – http://www.ourstory.info/library/4-ww2/Bourdelle/pbTC.html

Bourdelle Papers at Syracuse Libraries – http://library.syr.edu/digital/guides/b/bourdelle_p.htm

the art of asia in boston: introducing nancy li of tao select

Posted in Books I Love, Inspiration, tagged art, art history, Asian art, beauty, creativity, design, Edmund de Waal, family, fashion, Inspiration, interview, jewelry, Nancy Li, Photography, porcelain, TAO Select, The White Road on December 13, 2015| 1 Comment »

Nancy Li of TAO Selection

Image courtesy of artist.

Believe it or not, porcelain had been on my mind just before my chance encounter with Nancy Li of TAO Selection. I had come across a review of Edmund de Waal’s new book, The White Road. A noted potter, the book chronicles de Waal’s “journey into an obsession” to learn more about the origins and reinvention of porcelain. The prologue opens with de Waal in China: “I’m trying to cross a road in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province, the city of porcelain, the fabled Ur where it all starts …” Nancy Li is quick to tell you, and rightfully so, her family is from this region of China and that she is a third generation designer of porcelain.

Image courtesy of artist.

As I later told her, what I most admired about our first brief encounter outside of a church gift shop was her determination to find venues to market her jewelry, and also to share the story of her family and cultural heritage of working with porcelain. In his book de Waal writes of working with porcelain clay to make a jar. Though his studio is in South London, he writes, “… as I make this jar I’m in China. Porcelain is China. Porcelain is the journey to China.” During an interview, Nancy Li made a similar statement.

Image courtesy of artist.

We met briefly in Cambridge during her lunch break. Again, with great passion, she began sharing the story of her family especially of her grandfather, a porcelain master. For three generations the family and 15-20 employees have been working with clay using a proprietary process, molding it in forms from pendants to bowls to large statuary, hand-glazing and then firing the pieces in her family’s kiln. I’ve always thought of porcelain as fragile but porcelain can be strong as Nancy demonstrated by dropping a lovely blue and white bracelet on the floor. It made a beautiful ringing sound and remained unbroken.

On her website, Nancy describes attending the top fashion school in China, Donghua University. In talking with her I learned that six years ago she moved to the U.S. where she also received a Ph.D. in Materials Engineering from Boston University and a Management Degree from the MIT Sloan School of Management, part of her dual efforts to better understand the science behind porcelain and to raise awareness globally about the family business and the high-quality of the artwork produced.

Image courtesy of artist.

On top of her full-time job as a Systems Engineer, Nancy makes time to interact with people around Boston, educating them about porcelain and obtaining feedback about peoples’ fashion interests. She shares the feedback with her family, including producing sketches for alterations and new designs, inspired by what she hears and by her own artistic background.

She describes wanting to help people understand that high-quality porcelain is not only for the wealthy. It is not only something from the past to be found in antique stores. It is contemporary and it is art, an art that represents a culture. “Each piece of art has a story behind it,” she says at one point, holding a necklace in her hand. “It is art that inspires, that’s meant to be shown and shared. I think Americans have a wrong impression that everything made in China is cheap quality. What my family does in its local community, what it has been doing for so long, is of the highest quality and I want to share that work, our work, and help it evolve.”

Following are links to learn more about and connect with designer Nancy Li and to view more of her wearable porcelain art.

Following are links to learn more about artist and writer Edmund de Waal and his passion for porcelain.

interlude extra: erich stenger

Posted in Inspiration, tagged art, art history, Beaumont Newhall, books, cameras, collecting, Eric Stenger, Erich Stenger, history, Inspiration, Joseph A. Horne, Monuments Men, Museum Ludwig, Paul Vanderbilt, Photography, storytelling, World War II on March 1, 2015| 4 Comments »

Portrait Eric Stenger, 1906, Museum Ludwig, Foto (c) Rheinisches Bildarchiv

At the end of one letter, Dr. Erich Stenger writes, “I am up to my neck in work again and often regret that we did not get together more while you were here. There would have been so much more to show and to discuss. The director of the Kodak Museum B. Newhall has announced his visit. And when will YOU be returning to Germany?” (excerpt from 1950 letter from Stenger to Joseph A. Horne)

Erich Stenger (1878-1957) was a noted photographic historian and collector. He trained as a chemist. He worked during the early days of photography when photography was viewed more as a science rather than art. In 1905, he would join the faculty of the Technische Hochschule in Berlin as an assistant instructor in the photographic department. In the early 1900s, he co-wrote papers on The Fundamental Principles of Three-Colour Photography, and Radiation Sensitiveness of Silver Bromide Gelatin for White, Green and Orange Light. By 1934, he was named to the chair of photography founded in 1864 by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, a post he would retain until his retirement as Professor Emeritus in 1945. He began building his photography collection as a student and would do so until the end of his days.

Portrait Franz Grainer, 1920er Jahre, Museum Ludwig, FH 2438, Foto: © Rheinisches Bildarchiv

His collection was diverse, from landscapes to portraits, to decorative framed items to caricatures about photography. Beaumont Newhall wrote that “At the time of World War II, his collection was said to be the largest in private hands anywhere in the world.”

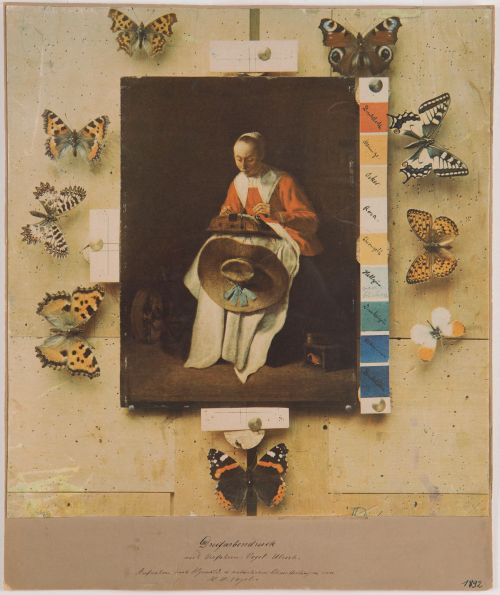

Hermann Wilhelm Vogel: Dreifarbendruck nach Verfahren: Vogel-Ulrich.

Aufnahme nach Ölgemälde und natürlichen Schmetterlingen 1892

Museum Ludwig, FH 10248, Foto: © Rheinisches Bildarchiv

Beaumont Newhall (1908-1993), referred to in Stenger’s letter, was a pioneering historian and first curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

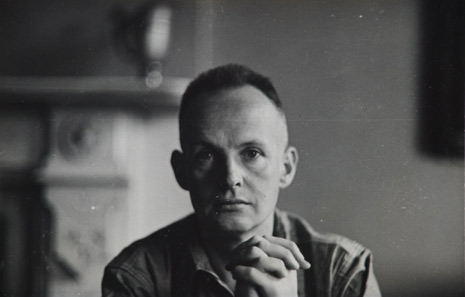

Beaumont Newhall, Self Portrait, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1970.

Over his career, he would write five editions of the signature work, The History of Photography. In 1945-1946, the Roberts Commission would recommend him as a good candidate for the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archive unit. Paul J. Sachs described Newhall “as one of the best men for library work.”

Newhall’s name appeared on one of the last lists of qualified officer personnel that the Roberts Commission presented to the War Department, indicating that “the only alternative after this is enlisted men.” Newhall would not be assigned to the unit. After discharge, Newhall returned to the U.S., continuing his research, lecturing, and curating photography exhibits. In 1948, he became the first Curator of Photography at the Kodak Eastman House in Rochester, NY and would serve as its director from 1958-1971.

One of those enlisted men who would join the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archive unit was Joseph Anthony Horne. And as part of that unit, Horne would meet Dr. Erich Stenger and learn of his unique photographic collection. Exactly when and where Horne first met Stenger in postwar Germany is unclear but the friendship they developed, as indicated through correspondence about everything from photography to family, would endure for a decade. That friendship must have stemmed from a mutual love of photography. Horne had been a photographer with the Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information (FSA-OWI).

Horne’s MFA&A colleague Paul Vanderbilt, during an Investigation Trip to Interview German Authorities and Inspect Private Papers, reports meeting Stenger in September 1946:

Vanderbilt recommended:

Horne certainly met Stenger at a December 1946 meeting of photographers and photographic scientists “to discuss the present situation of the photographic trade and industry in Germany.” Mr. Horne had been invited to attend by the Berlin Press Photographers Guild. In his report following the meeting, he echoed Vanderbilt’s recommendations that Stenger be aided in reassembling his photographic collection, a collection spread across a divided postwar Germany.

Germany Occupation Zones 1946

It is unclear from available records how helpful Horne, Vanderbilt and the other Monuments Men were in helping Dr. Stenger rebuild his collection in a post-war, rapidly becoming Cold War, world. What is clear is that this unit of librarians, archivists and those dedicated to preserving and sharing knowledge, felt strongly about helping this gentleman as much as they could.

As the socio-political landscape of Europe changed, and with it the U.S. presence, Horne prepared to move on to other positions within the U.S. foreign services. Regardless, he and Stenger stayed in touch, corresponding about family and photography, and perhaps even their shared interest in stamp collecting. Horne would highlight opportunities for Stenger to exhibit photography, and Stenger provided updates on the health of his collection.

“The day after tomorrow I will be going to Switzerland, where I have been asked to come to deliver a few scientific lectures. I will be back home in mid-November. While in Switzerland, where I used to make annual purchases from merchants who knew what I was collecting, I will once again be on the look-out for my collection. Not having been back in eleven years, most of the merchants won’t remember me. Recently I was able to acquire some very special objects here in Germany; considering the awful destruction, I marvel that here and there something useful still pops up.” (excerpt from 1950 letter from Stenger to Joseph A. Horne)

Henry Traut, Porträt, München, Museum Ludwig,

1932, Foto: Rheinisches Bildarchiv

In 1955, Stenger’s diverse collection was purchased by the company Agfa, and today it complements a number of other collections as part of the Photographic Collection of the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. Stenger died in September 1957, and as Beaumont Newhall states in a later editorial, the world of photography lost a foremost historian and collector.

Sources and Additional Readings

The Photographic Collection of the Museum Ludwig

Image Magazine, 1958, incl. editorial on Dr. Erich Stenger

press page about the Stenger Collection

About Beaumont Newhall (International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum)

Beaumont Newhall (Scheinbaum & Russek LTD)

Oral History Interview Beaumont Newhall

leaves in the abstract

Posted in Inspiration, Nature Notes, tagged abstract, art history, beauty, colors, imagination, Inspiration, leaves, nature, Photography, Tamara de Lempicka, women artists on February 24, 2015| 1 Comment »

When I saw these out of focus leaves — their form, shape, the melding of colors — I could not help but be reminded of the artwork of Tamara De Lempicka and her paintings, full of color, and the fall of light and shadows such that some things are revealed and the rest is left entirely to imagination.

As I was trying to learn more about the artist, I came across this website produced by family and friends. I especially enjoy the artwork page providing the opportunity to scroll through, by decades, her life story in words and images. Enjoy.

update: interlude TOC

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged art, art history, artwork, culture, interlude, interludes, Joseph A. Horne, life, military history, storytelling, war on June 3, 2014| 13 Comments »

Following is an updated table of contents (TOC) for the series of interludes, a collection of historical vignettes, threaded together by following in the footsteps of one gentleman, Joseph A. Horne (1911-1987). It’s a glimpse into history that continues to shape this world. It’s been a wonderful, sometimes surprising, experience for me. The interludes will conclude over the next few months including a few more “interlude extras.” I hope you enjoy this journey of words and images.

I. interludes TOC

iii. interlude: exodus, part 1

v. interlude: dust in the wind

vii. interlude: to protect, preserve, and return … if possible

viii. interlude: offenbach archival depot

II. interlude extras

interlude extra: arnold genthe

interlude extra: edward gordon craig

interlude extra: washington labor canteen, eleanor roosevelt and race relations

interlude extra: erich stenger

interlude: to protect, preserve and return … if possible

Posted in Inspiration, tagged architecture, art history, Cordell Hull, culture, degenerate art, George Stout, military history, Monuments Men, Offenbach Archival Depot, Photography, storytelling, World War II on June 3, 2014| 7 Comments »

Nearly one-year after U.S. entry into World War II, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt would receive a letter from Harlan F. Stone, Chief Justice of the United States. He shared the concerns of many in the art and architectural fields at the destruction taking place in Europe.

Bombing of Hamburg, 1943

While Germany must, of course, be defeated, Stone and the others were urging the development of an organization charged with the protection and conservation of European works of art. The organization would aid “in the establishment of machinery to return to the rightful owners works of art and historic documents appropriated by the Axis Powers.”

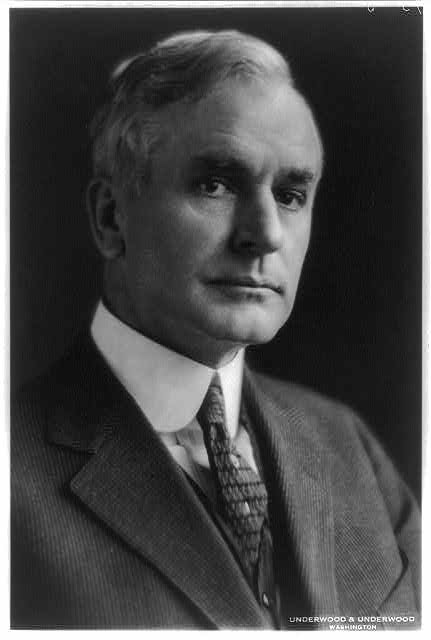

Cordell Hull, U.S. Secretary of State

By 1943, FDR would establish this American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in Europe, its intent to operate for three years and to cooperate with the appropriate branches of the Army, Department of State and civilian agencies. Secretary of State Cordell Hull recommended that it be headquartered at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

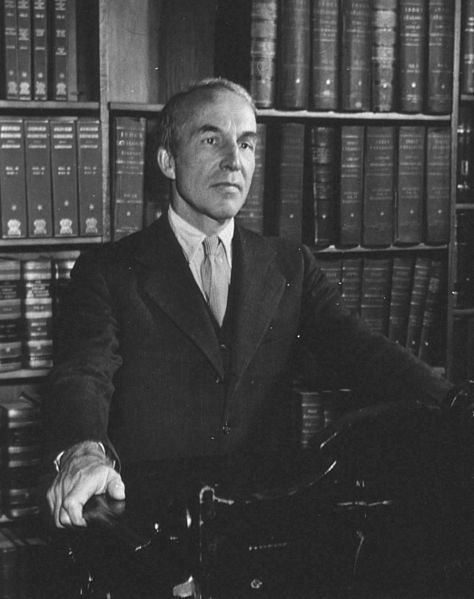

Archibald MacLeish, 1944

The Commission would include Archibald MacLeish, Librarian of Congress, Paul J. Sachs, Asst. Director of the Harvard Fogg Museum, and Francis Henry Taylor, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Using this group’s networks of former students, colleagues and peers, experts would be sought to volunteer and help the Commission complete two functions:

Even prior to U.S. involvement in the war, efforts had been made to catalog endangered art and historic monuments. Card files were also compiled of scholars and specialists in the Fine Arts, Books and Manuscripts. All information was considered significant, from scholarly skills to possible political leanings.

Detailed maps were created and/or collected showing areas to be spared, if at all possible, and aerial photographs were taken.

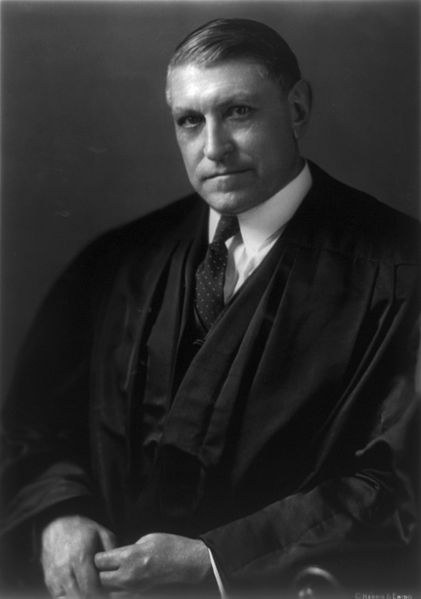

By April 1944, recognizing the need to prepare maps for the protection of art and historic monuments in Asia, as well, the Commission’s name would be altered, and the words “War Areas” would replace “Europe.” In August, Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts would become Commission chair. Roberts was one of three Supreme Court Justices to vote against the plan for internment of Japanese Americans during the war. Over time the Commission would simply be referred to as the Roberts Commission.

Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts

The Roberts Commission would establish the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Unit (MFA&A) within the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied Armies. Eventually numbering over 300 men and women, the unit’s “Monuments Men” included architects, archaeologists, art historians, artists, curators, and librarians. During the war, they would be assigned in small numbers to Allied troops in the field.

George Stout

Monuments Men had to be fluent in the languages of the places where they were to be assigned. And to appease concerns about shifting manpower away from fighting forces, they had to be older than the age for fighting eligibility, so most were in their thirties or older. Early days for the Monuments Men, as they traveled with Allied troops, were difficult since they had little authority or supports in place. That would change somewhat over time as Allied leadership including MacArthur in the Pacific and Eisenhower in Europe made clear that cultural preservation was a priority, though never one to outweigh the protection of soldiers’ lives.

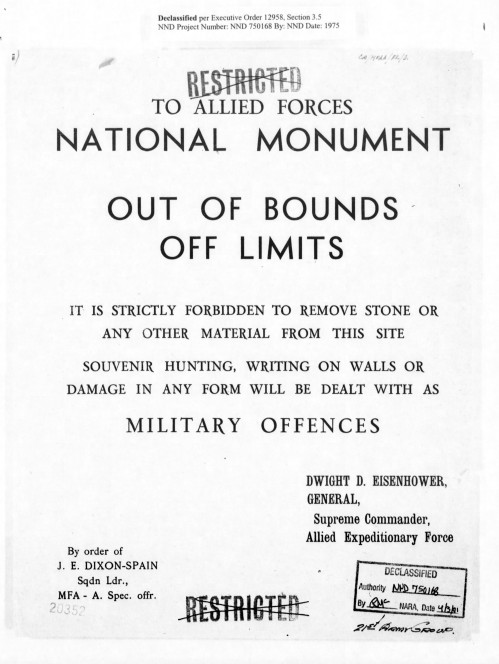

American Zone Poster

The preservation and protection of artistic and historic monuments would take place differently in the two different theaters of World War II — Europe and the Pacific. In Europe, even before the war ended, there would be a focus by Monuments Men like Mason Hammond, George Stout and others on recovering the artwork and cultural items taken by Hitler and the Nazis from wealthy Jewish families, museums, university libraries and religious institutions. The goal: to protect and preserve these cultural assets, and to prevent the Germans from using the stolen loot to fund German war efforts.

As early as 1937, Hitler’s intentions to use art as propaganda had been clear. Expressionist and modern art was labeled as degenerate. Those works not sold or destroyed outright were paraded for years in exhibits extolling their worthlessness. Less than a decade later, these same works would be celebrated in the U.S. National Gallery and other museums around the world.

MFAA Officer James Rorimer supervises U.S. soldiers recovering looted paintings from Neuschwanstein Castle

But before those works of art and their creators would be celebrated, the war in Europe had to end which it did in May 1945. As the Allied forces settled in, the Monuments Men continued to fan out, recovering art, and beginning the long process of cataloging and restitution. In the Pacific theater, the war would end in August.

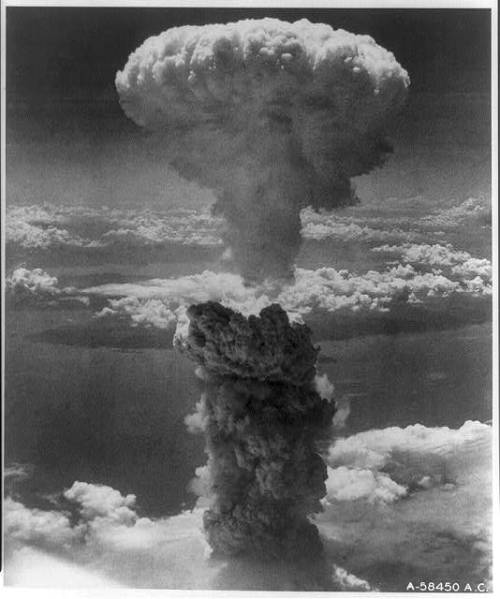

Hiroshima 1945

On August 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima. “The explosion wiped out 90 percent of the city and immediately killed 80,000 people; tens of thousands more would later die of radiation exposure. Three days later, a second B-29 dropped another A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people.” On August 15th, Emperor Hirohito would announce surrender.

Nagasaki Under Atomic Bomb, 1945

Into this devastated, postwar landscape, Monuments Men like Lt. Walter D. Popham would document damage done by the war and make suggestions for recovery and future protection of cultural assets. Popham was a noted landscape architect and professor prior to the war. He’d written books on the gardens of Asia including the tree-lined strees of Tokyo. George Stout, respected for his work as a Monuments Man in Europe, was especially pleased to learn of Popham’s Japan assignment. Stout had been one of several Monuments Men to recommend deploying the Monuments Men in Japan after its surrender.

The effort of the Monuments Men in Japan and across Asia is one that remains to be shared more widely. Peruse just a few of the catalog cards, filed in the National Archives, in which Popham and others describe their perceptions of the postwar Japanese landscape, and their interactions with the populace, it is clear that many stories remain to be told.

With the war’s end, in both Europe and Asia, the role of the Monuments Men would shift. Governments mobilized to literally rebuild whole nations. How could one balance (and budget for) the collection, preservation and restitution of artwork while meeting the immediate needs of feeding, clothing and housing millions of displaced peoples? Former allies were clearly becoming enemies. What role could art have, if any, in forging new bonds or cementing old ties?

In Europe, by the spring of 1946, three central collection points were firmly established in Germany, in Wiesbaden, Munich and Offenbach. The Offenbach Archival Depot would specialize in collecting and cataloging Jewish cultural items, books and archives. The establishment of Offenbach was led by archivist Lt. Leslie Poste. One of his assistants was Joseph A. Horne.

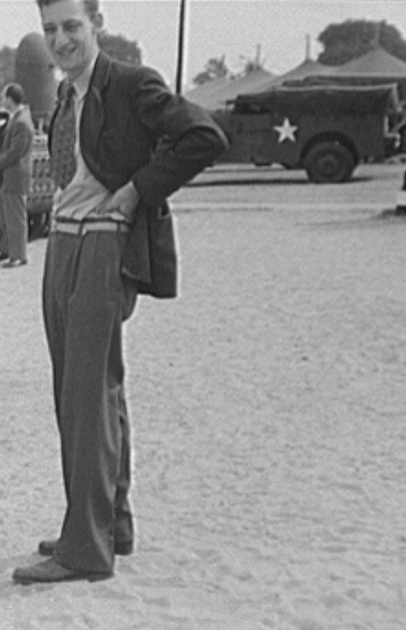

Joseph A. Horne, 1940s

By February 1947, Horne would become the depot’s third director. According to the memoirs of Lucy Dawidowicz, his friends called him Tony. “Before the war, he’d been on the staff of the Library of Congress’s photographic division. Transferred from the MFA&A in Berlin, he was then new to the Depot, having taken over his duties barely two weeks before my visit. About thirty, very tall, thin, lanky, and blond, he was the only American there. He was in charge of a staff of some forty Germans.”

His tenure would coincide with one of the worst winters to strike Europe in recent memory. The Cold War with the Russians was dawning. The restitution (or not) of artwork and cultural items was to become a strategic tool used by military intelligence and policymakers on all sides. Individuals, including war survivors as well as surviving relatives of those killed by the Nazis, universities and museums whose collections had been sacked … their demands for restitution and return of art, books and cultural items poured in. Horne, like many others, would deal with these requests as respectfully as he could even as events unfolded around him that would place Offenbach at the center of one of the most unexpected efforts to return looted cultural items to Jewish communities around the world.

More to follow in July…

Sources/Additional Reading

World War II records from the National Archives searchable here

More information about Hamburg photo

Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, History.Com

About Mason Hammond, First Monuments Man in the Field

World War II Photography Database