Hard to believe it was nine years ago that Mr. Langosy allowed me to share the story of his art. What a remarkable man and such a pleasure to have known him and his family. Donald Langosy passed away this week and what a legacy he leaves behind. An active artist until the end, his last exhibit, The Journey of Eduardo Gunkla, is currently on display at the Multicultural Arts Center in Cambridge, MA, until January 9th. A virtual gallery is also accessible online. https://multiculturalartscenter.org/eduardo-gunkla/

Posts Tagged ‘poetry’

9 years ago …

Posted in Inspiration, tagged art, disability, fine art, Inspiration, painting, poetry, storytelling on January 6, 2026| 1 Comment »

“the land that never has been yet”

Posted in Inspiration, tagged american dream, American history, black history, history, Inspiration, Langston Hughes, Photography, poetry on September 2, 2025| 4 Comments »

Here’s a challenge. In this age of quick reads, read this whole poem, Let America Be America Again, by Langston Hughes. Indeed try reading passages out loud. Written about 90 years ago, it could have been written today. And therein lies the sadness and yet the hope. Read on …

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/147907/let-america-be-america-again

autumn, a guest post

Posted in Guest Contributor, Inspiration, tagged autumn, beauty, colors, Inspiration, landscape, Maine, nature, nature photography, New England landscape, Photography, poem, poetry, prose on October 18, 2021| 5 Comments »

When I saw Donna’s photos from Lovell, Maine I knew I wanted to share them and so I asked her for some words to accompany them. She shared a poem written by her partner’s daughter, Kristin Roberts, and suggested Kristin’s words might work instead. A perfect pairing. The poem, written by Kristin in the 7th grade, attests to her sensitivity and great observational skills about nature, about the people who engage with the Lovell landscape, and about the passage of time. Please enjoy this lovely pairing of words and images that capture the season.

Autumn

Crimson, buttercup, marigold leaves swirl rustling around in rhythm of Autumn. The icy winds swipe.

Bee charmers with nets on their crowns, collect the pure golden honey from dripping cones. Farmers collect apples just before the tart crispy fruit turns to ripe.

The bitter winds nip at my face, redden my cheeks, numb my fingers, while icy blue Jack frost freezes Queen Anne’s lace.

Warm golden summer’s gone.

Oaks and birches are stripped bare. Rifle shots ring out in echo as sharp eyed hunters bring down swift graceful deer.

Sweet singing birds long ago flew south, replaced with huge black crows with their loud mocking mouths.

Soft fluffy snow will soon replace corpsed grass. And the awful sight soon will pass.

My lawn is littered with bright leaves, each unique in its own way. Dark misty evening is extended. Gray dawns are gloomy, bright mornings have ended.

Brilliant gay summers will be here at last, when the silver season after golden Autumn soon comes to pass.

by Kristin Roberts (1981-2011)

watermelon pickle

Posted in Inspiration, tagged family, Inspiration, memories, musings, nostalgia, personal, poetry, ramblings, storytelling, watermelon on July 22, 2019| 2 Comments »

This is a ramble with no meaning except I felt a need to put fingers to the keyboard and share an experience from this day. I’ve been saving watermelon rind trying to decide if I will try to make some watermelon pickles. Now, I have never eaten such a pickle in my life though when I was little I used to admire their beauty in big jars on store counters. As a child I ate plenty of the fruit itself. My oldest brother still reminisces about the big ones with the big black seeds. I think I remember watermelons so big I could sit on them. Those are hard to find. Small, round, seedless (and in my humble opinion oftentimes tasteless) has become the store norm. I’ve lost my taste for watermelon flesh though I’ve been buying watermelon slices of late. Not for me but for a certain person in my life who needs to drink more water but doesn’t and so I simply place saucers of sliced cold watermelon in front of him. Hydration is hydration.

But now I have these rinds … and I’m in a creative place in my life right now … and so I told him I might try my hand at pickles. And when this person heard my intentions, he remembered words from a poem. “Reflections on a gift of watermelon pickles,” he said. We looked it up, a poem by John Tobias. As I began to read it out loud, Steve, who has a wicked memory for poetry, stopped me to say, “I don’t think I’ve ever actually read the poem. I just know those few words.” And so I finished reading the poem and he was silent and when I looked up I saw that he had been moved to tears.

I think my big brother who is near Steve’s age would cry too. Not so my 12-year old friend. Her response to reflections on a life lived would be quite different than people five decades older. This is a rambling post with no photographs because there is no photograph that can compare to the rich imagery embedded throughout the poem … except maybe one day I’ll come across one of those big ol’ watermelons and split it open and let the sun shine on the pink flesh, black seeds and white rind … and maybe that would be an appropriate pairing of image with the following words. We’ll see …

Reflections on a Gift of Watermelon Pickle Received from a Friend Called Felicity

During that summer

When unicorns were still possible;

When the purpose of knees

Was to be skinned;

When shiny horse chestnuts

(Hollowed out

Fitted with straws

Crammed with tobacco

Stolen from butts

In family ashtrays)

Were puffed in green lizard silence

While straddling thick branches

Far above and away

From the softening effects

Of civilization;

During that summer–

Which may never have been at all;

But which has become more real

Than the one that was–

Watermelons ruled.

Thick imperial slices

Melting frigidly on sun-parched tongues

Dribbling from chins;

Leaving the best part,

The black bullet seeds,

To be spit out in rapid fire

Against the wall

Against the wind

Against each other;

And when the ammunition was spent,

There was always another bite:

It was a summer of limitless bites,

Of hungers quickly felt

And quickly forgotten

With the next careless gorging.

The bites are fewer now.

Each one is savored lingeringly,

Swallowed reluctantly.

But in a jar put up by Felicity,

The summer which maybe never was

Has been captured and preserved.

And when we unscrew the lid

And slice off a piece

And let it linger on our tongue:

Unicorns become possible again.

by John Tobias

on a prayer book

Posted in Inspiration, tagged American history, art, black history, faith, history, Inspiration, poetry, religion, resistance on June 20, 2018| 1 Comment »

Christus Consolator by Ary Scheffer, 1851

Following is the last stanza of a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier written in 1859 but with a relevance for this day as well:

O heart of mine, keep patience! Looking forth,

As from the Mount of Vision, I behold,

Pure, just, and free, the Church of Christ on earth;

The martyr’s dream, the golden age foretold!

And found, at last, the mystic Graal, I see,

Brimmed with His blessing, pass from lip to lip

In sacred pledge of human fellowship;

And over all the songs of angels hear;

Songs of the love that casteth out all fear;

Songs of the Gospel of Humanity!

Lo! in the midst, with the same look He wore,

Healing and blessing on Genesaret’s shore,

Folding together with the all tender might

Of His great love, the dark hands and the white,

Stands the Consoler, soothing every pain,

Making all burdens light, and breaking every chain.

Whittier wrote the poem in response to a publisher producing a book of prayer with a cover image of Ary Scheffer’s painting Christ Consolator … but with the image of the enslaved black man removed.

In preface to the poem, Whittier wrote: “It is hardly to be credited, yet is true, that in the anxiety of the Northern merchant to conciliate his Southern customer, a publisher was found ready thus to mutilate Scheffer’s picture. He intended his edition for use in the Southern States undoubtedly, but copies fell into the hands of those who believed literally in a gospel which was to preach liberty to the captive.”

John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892) and broadsheet of his poem Our Countrymen in Chains

Described as a Quaker, poet and abolitionist, Whittier wielded words as a warrior poet to fight for the end of slavery. A literary giant and inspiration to many, it was his friendship with two people that enabled me to learn about his poetic response to someone’s efforts to rewrite history by altering a work of art.

Lucy Larcom (1824-1893) and Phillips Brooks (1835-1893)

Lucy Larcom was a respected teacher, poet and author. Based on her letters and biographies, throughout her life, she grappled with spirituality and religion. After hearing Phillips Brooks sermons at Trinity Church in Copley Square, they began a correspondence that developed into a deep friendship. He became a religious guide in her life. She was also close friends with Whittier. In one of her letters to Whittier, in 1892, she wrote:

“I have always thought of thee as a spiritual teacher. And then in late years to have had in addition the teachings and friendship of Phillips Brooks has been a great and true help. I thank God that you two men live and, “will always live,” as he says to you, and that I have known you both. When [Brooks] called at Mrs. Spaulding’s after seeing you, he told us about the Ary Scheffer poem and repeated it to us from the words “O heart of mine,” through to the end, as he went away, standing before the picture — Christus Consolator,” which hangs at her parlor door …”

All three of these literary figures died within a few months of each other. Lucy Larcom was the last and she writes … yes, poetically … about the loss of each of these men and her gratitude for their guidance in her life. It was but random chance finding her letters online that enabled me to revisit Whittier’s works and appreciate how, like Brooks in the pulpit, he used words to make a difference. An endless need across time …

Sources & Additional Reading

Lucy Larcom: Life, Letters, and Diary by Daniel D. Addison, 1894.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucy_Larcom

Full text of On a Prayer Book by John Greenleaf Whittier, 1859.

Our Countrymen in Chains by John Greenleaf Whittier, 1842

temporarily mute

Posted in Inspiration, tagged Emma Lazarus, freedom, hope, immigration, Inspiration, musing, National Poetry Month, opinion, poetry, refuge, Statue of Liberty on April 30, 2018| 3 Comments »

Eventually I had to mute the television. I could not listen to his voice, and so I watched him speak. I watched him gesticulate wildly. I watched him make the schoolboy faces suggestive of a naughty teen making fun of others and which brings out the naughtiness of the other schoolboys who laugh though they mostly know they should know better. But since there’s no one around to hold any of them accountable, why not poke a little fun, right?

I watched the people behind him bathed in his dark light, their own eyes fiercely bright, as they gave praise to that which stood before them … this bold entity that made them feel good! Trump was nothing like them and yet in their minds they saw themselves or what they sought to be. A white man of inherited privilege and of wealth speaking crudely and with malice about all that was not wealthy and white and not American based on a skewed view of what it means to be American.

And what does it mean to be American? What would happen if every member of Congress had to sit and compose a 500-word essay on the subject? The President and V.P. could do it as well. How about everyone who is a member (so far) of the President’s cabinet? Or maybe better yet, as a writing prompt, have them each read the following poem by Emma Lazarus and respond to it in writing. Full sentences. No tweets. No emojis. Wouldn’t that be something to see?

riverine poetry

Posted in Branches, Inspiration, Nature Notes, tagged Charles River, Inspiration, National Poetry Month, nature, Photography, poetry, rivers, urban landscape on April 12, 2018| 1 Comment »

It was a windy day when I recently walked along the Charles River. The river itself did not move very fast. The water was low and though it be mid-April, all around were the dead leaves of the previous seasons. Only a few daffodils brightened the shore. I decided to work with what I had and so I photographed the leaves in their watery haunt. Most of the images didn’t come out, at least to my liking, but this one seemed rather poetic to me.

poetry and the poetic, part two

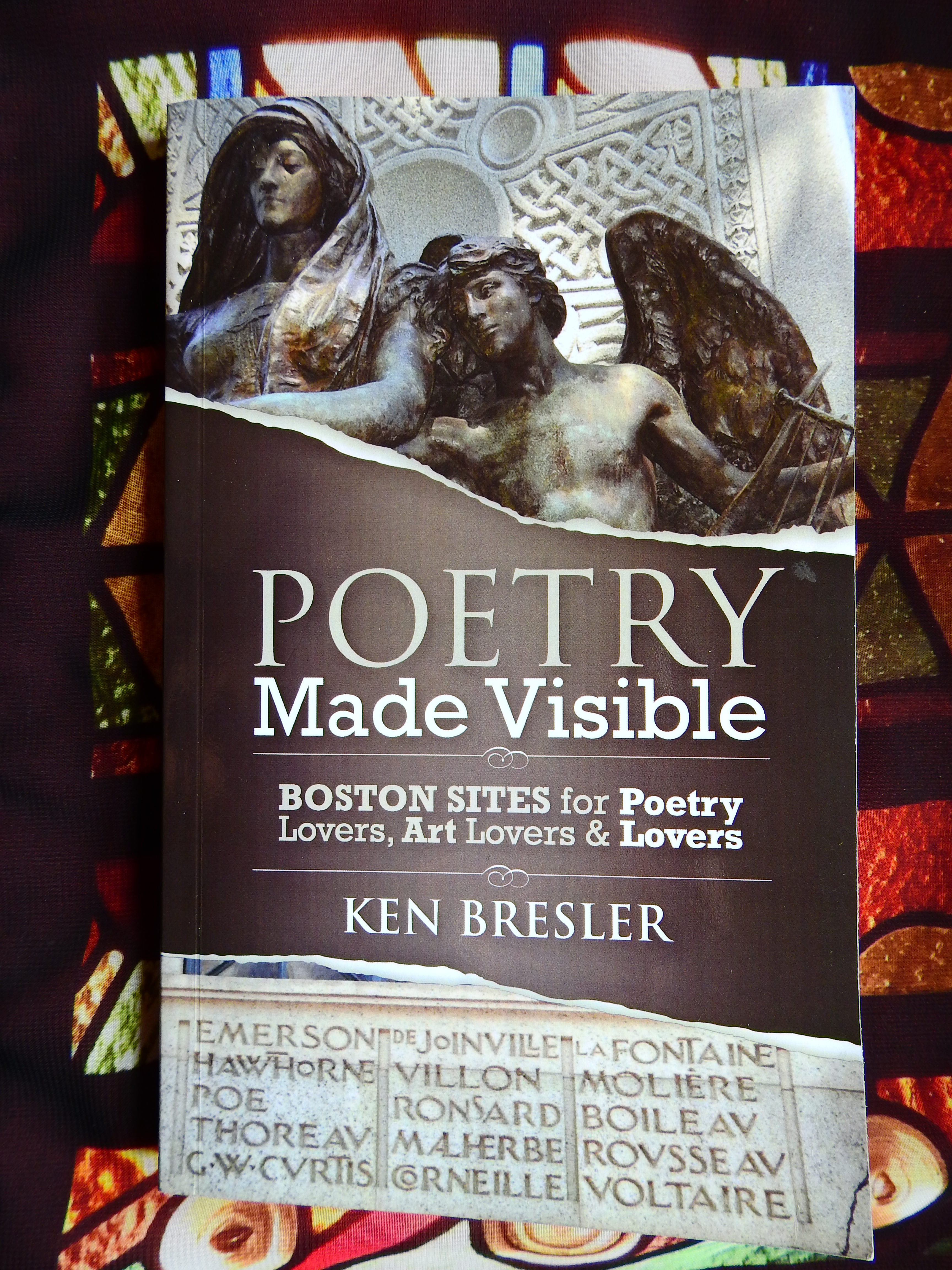

Posted in Inspiration, On the Road, tagged art, book review, guidebook, Inspiration, National Poetry Month, Photography, poetry on April 8, 2018| Leave a Comment »

Poetry Made Visible (2017) is described as “a guidebook for tourists and natives of the Boston Area, for students and teachers, for lovers of poetry and lovers of public art.” Well, in order to review the book and write about it, I knew I had to use the book. So I began with the first chapter focused on the main branch of the Boston Public Library in Copley Square. As I walked around what Bresler refers to as “the temple of poetry,” an amazing thing began to happen. I walked around the library with an open book, reading, pausing, looking, and guess what? People began to notice me. They too paused and looked and, since they had no book in-hand, their brows furrowed as they tried to see what I might be seeing, carved into stone or sculpted into a door.

Poetry with her halo, McKim building door

As I traveled around the library, I found myself engaging with librarians. While Bresler does an amazing job of pointing out the poetry integrated into the library’s exterior and interior structure, the challenge is that the Boston Public Library’s interior design is quite dynamic and in the past year there have been major renovations and redecoration. So I had to converse with the librarians to ascertain where certain sculptures had been moved because the book’s walking directions don’t always match up.

Dare I say that I believe that the librarians had a great time helping me to track down the various sculptures mentioned, and peering into the book because it was a resource that was helping them to see their building with fresh perspective. And I think that’s the strength of this book. As the title suggests, Bresler truly does make poetry visible. I’ve lived in Boston long enough that I take the Boston Public Library for granted, but with his book in-hand I paused and peered up and truly looked at what was there. And so did the little kid next to me.

Throughout the book he asks thought-provoking questions. They cannot be answered by “yes” or “no.” One must actually pause, ponder, reflect. I can imagine a teacher or a parent using excerpts of this book to help guide their students or children in seeing the world around them and exploring how something done so long ago, whether the poem or the sculpture, has relevance to their lives today.

Maya Angelou Bust in Boston Public Library

“You’ve heard of a date movie? This is a date book.” So it says on the back cover. Well, when you look at the list of Dispersed Sites of poetry that he has compiled, I can see that it would be fun to make a date with a friend to see a site, to reflect upon the poets remembered, and the contemporary artists capturing their spirit in stone and more.

As has the Boston Public Library, the City of Boston and surrounding areas will continually change. I do hope that the sculptures and other public artworks that Bresler has captured survive over time. I think Bresler’s book is a wonderful reminder of the literary heritage of the Greater Boston area and the important role of poetry in society.

Poetry Made Visible: Boston Sites for Poetry Lovers, Art Lovers & Lovers

poetry and the poetic, part one

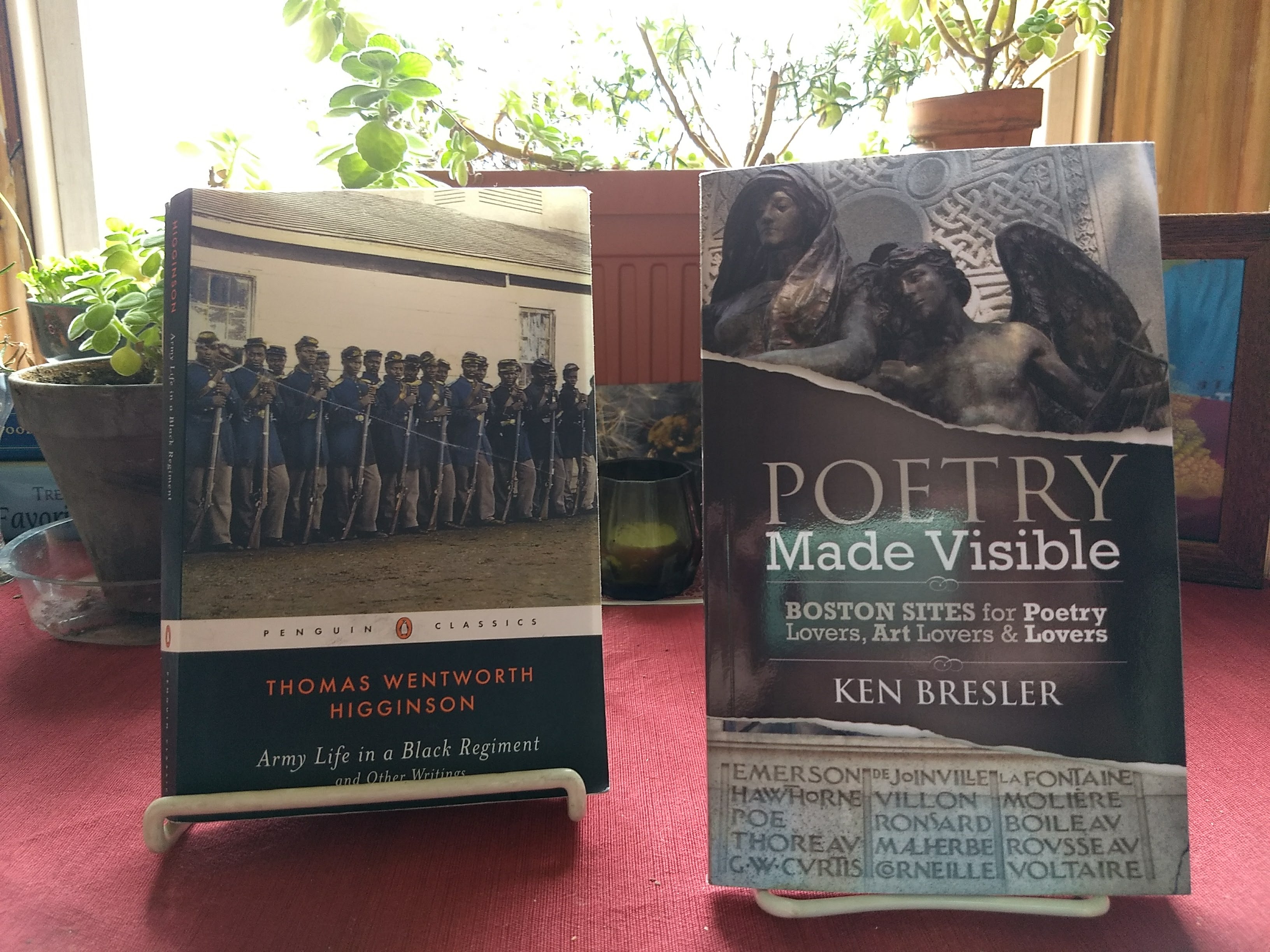

Posted in Books I Love, Inspiration, tagged African American history, book review, books, civil war, Inspiration, memoir, military history, National Poetry Month, Photography, poetry, storytelling, thomas wentworth higginson on April 2, 2018| Leave a Comment »

There’s one positive to the long winter/long early spring commutes in Boston when your primary form of transportation is the train and bus. Plenty of time to read. Two books have been in my bag of late that I’d like share in some fashion. Very different books, indeed, but there is a common thread of poetry and the poetic. First up, Army Life in a Black Regiment, first published in 1869.

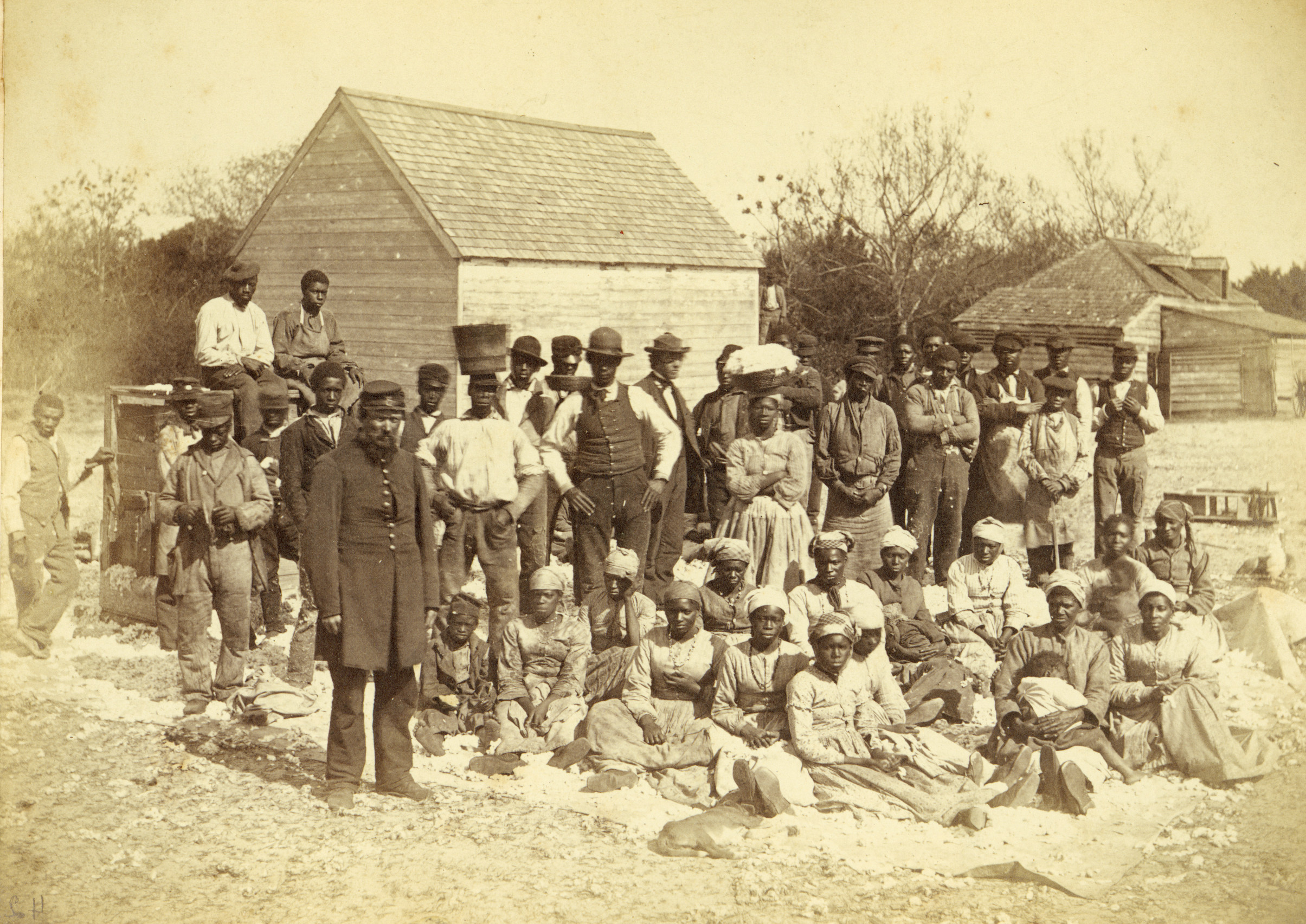

In November 1861, shortly after the start of the U.S. Civil War, the Union fleet took command of Port Royal, South Carolina and neighboring sea islands including St. Helena and Hilton Head. Plantation owners fled leaving behind 10,000 slaves, and a bumper crop of sea island cotton.

A project was conceived known as the Port Royal Experiment. Its purpose? By working with this group of 10,000 freed slaves, in a relatively contained area, perhaps solutions could be found for the greater looming challenge of how to integrate into society millions of emancipated slaves.

At least three different groups were involved in the experiment, including Northern missionaries who focused on education and training, entrepreneurs who wanted to show the profitability of free labor versus slave labor, and the U.S. government which, most immediately, needed more men on the battlefield. These groups sometimes worked together but were more often at odds. For an excellent scholarly analysis of the Port Royal Experiment, please read Willie Lee Rose’s Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment.

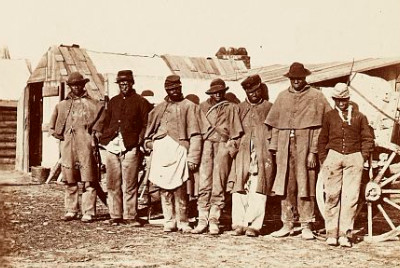

port royal students

Teachers immediately went to work setting up schools. Entrepreneurs began implementing their free labor experiment offering to pay the former slaves to cultivate the cotton. But as for volunteering to fight for the military?

escaped slaves wearing old union uniforms

Since the beginning of the war, Union officers in the field saw the need for trained black troops. Early attempts to recruit had met with poor results and had little initial support from Lincoln’s White House. But finally, with Port Royal, a new more coordinated effort was to be made. In November 1862, Thomas Wentworth Higginson received a letter from Brigadier General Rufus Saxton. “I am organizing the First Regiment of South Carolina Volunteers, with every prospect of success. Your name has been spoken of, in connection with the command of this regiment, by some friends in whose judgement I have confidence. I take great pleasure in offering you the position of Colonel in it … I shall not fill the place until I hear from you …”

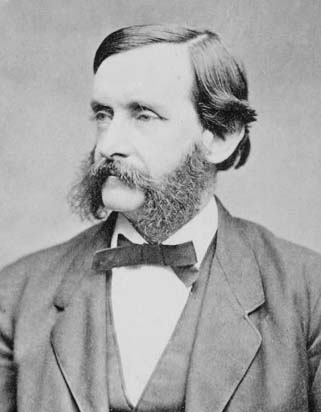

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Higginson was a poet, biographer and novelist as well as a Unitarian minister. From a prominent, wealthy New England family, he had long been a staunch abolitionist, social reformer and a major supporter of John Brown. Once the Civil War began, he joined the Union Army. Though he already served another regiment, he accepted Saxton’s invitation to visit Port Royal. He doubted he would accept the commission but, after meeting the people, he accepted his new role without hesitation.

During his time with the regiment he would record detailed entries in his diary about the people, the Sea Island landscape, and of course about the regiments military actions. After becoming ill, in 1864, he would return to New England, resign his commission, and resume researching and writing. Essays about his wartime experiences with the First Regiment appeared infrequently in the Atlantic. By 1869, he compiled the essays, diary excerpts and other work into the book, Army Life in a Black Regiment and Other Writings.

First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry

In the introduction to his diary entries, Higginson tells the reader:

“I am under pretty heavy bonds to tell the truth, and only the truth; for those who look back to the newspaper correspondence of that period will see that this particular regiment lived for months in the glare of publicity, such as tests any regiment severely, and certainly prevents all subsequent romancing in its historian. As the scene of the only effort on the Atlantic coast to arm the negro, our camp attracted a continuous stream of visitors, military and civil. A battalion of black soldiers, a spectacle since so common, seemed then the most daring of innovations, and the whole demeanor of the particular regiment was watched with microscopic scrutiny by friends and foes. I felt sometimes as if we were a plant trying to take root, but constantly pulled up to see if we were growing.”

“Of discipline there was great need … Some of the men had already been under fire but they were very ignorant of drill and camp duty. The officers, being appointed from a dozen different States … had all that diversity of methods which so confused our army in those early days. The first need, therefore, was an unbroken interval of training. During this period, which fortunately lasted nearly two months, I rarely left camp … Camp life was a wonderfully strange sensation to almost all volunteer officers, and mine lay among eight hundred men suddenly transformed from slaves into soldiers …”

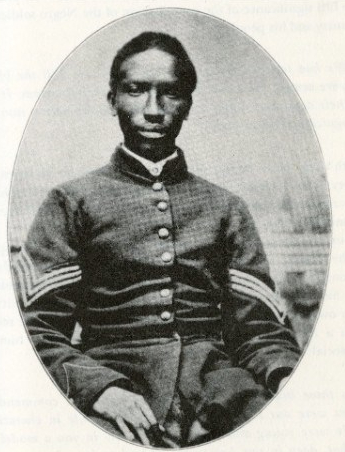

Infantry Members

Each subsequent diary entry reveals Higginson’s poetic nature. “Yesterday afternoon we were steaming over a summer sea, the deck level as a parlor-floor, no land in sight, no sail, until at last appeared one light-house … The sun set, a great illuminated bubble, submerged in one vast bank of rosy suffusion; it grew dark; after tea all were on deck, the people sang hymns; then the moon set, a moon two days old, a curved pencil of light, reclining backwards on a radiant couch which seemed to rise from the waves to receive it…”(November 24, 1862)

Dress Parade of the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry

“… One adapts one’s self so readily to new surroundings that already the full zest of the novelty seems passing away from my perceptions, and I write these lines in an eager effort to retain all I can. Already I am growing used to the experience, at first so novel, of living among five hundred men, and scarce a white face to be seen, — of seeing them go through all their daily processes, eating, frolicking, talking, just as if they were white. Each day at dress-parade I stand with the customary folding of the arms before a regimental line of countenances so black that I can hardly tell whether the men stand steadily or not; black is every hand which moves in ready cadence as I vociferate, “Battalion! Shoulder arms!” nor is it till the line of white officers move forward, as parade is dismissed, that I am reminded that my own face is not the color of coal.” (November 27, 1862)

Infantry Member Henry Williams

Higginson paints a poetic picture of both people and place. “All the excitements of war are quadrupled by darkness; and as I rode along our outer lines at night, and watched the glimmering flames which at regular intervals starred the opposite river-shore, the longing was irresistible to cross the barrier of dusk, and see whether it were men or ghosts who hovered round those dying embers. I had yielded to these impulses in boat-adventures by night … and fascinating indeed it was to glide along, noiselessly paddling, with a dusky guide, the reed-birds, which wailed and fled away into the darkness, and penetrating several miles into the interior, between hostile fires, where discovery might be death.”

The book is a time capsule chronicling an important period in American history. These soldiers predated the more famous Massachusetts 54th regiment led by Robert Gould Shaw. Higginson brings to life the courage, the ingenuity and discipline of these early troops. He shows them to be as human as their white counterparts, their brothers in arms. And though the people of the Sea Islands, for the most part, had known nothing other than slavery, they were prepared with the right training to fight for and defend their freedom and that abstract thing known as “the Union” that their labor had sustained for generations.

Higginson’s book reminded me of the unique nature of the Sea Islands, a uniqueness that Higginson remarks upon in a post-war essay about the Negro as a Soldier. “I had not allowed for the extreme remoteness and seclusion of their lives, especially among the Sea Island. Many of them had literally spend their whole existence on some lonely island or remote plantation, where the master never came, and the overseer only once or twice a week.”

Under these conditions the slaves developed a patois that is now known as Gullah, a blending of standard English and its Southern regionalisms with different West African languages. By the time the Civil War began, there were over 400,000 slaves in South Carolina alone. Such a large investment in labor was needed for the labor intensive yet highly profitable cultivation of cotton and especially rice.

During one expedition along the Edisto River with his now-trained troops, Higginson confronts the enemy near some of these rice fields.

“The battery — whether fixed or movable we knew not — met us with a promptness that proved very short-lived. After three shots it was silent, but we could not tell why. The bluff was wooded, and we could see but little. The only course was to land, under cover of the guns. As the firing ceased and the smoke cleared away, I looked across the rice-fields which lay beneath the bluff. The first sunbeams glowed upon their emerald levels, and on the blossoming hedges along the rectangular dikes. What were those black dots which everywhere appeared? Those meadows had become alive with human heads, and along each narrow path came a straggling file of men and women, all on a run for the riverside. I went ashore with a boat-load of troops at once. The landing was difficult and marshy. The astonished negroes tugged us up the bank …They kept arriving by land much faster than we could come by water … What a scene it was! With the wild faces, eager figures, strange garments, it seemed, as one of the poor things reverently suggested, [like judgment day]. “

“Bless you” and “Bless the Lord,” were the exclamations Higginson remembers hearing over and over again. “Women brought children on their shoulders; small black boys carried on their backs little brothers … Never had I seen human beings so clad, or rather so unclad … How weak is imagination, how cold is memory, that I ever cease, for a day of my life, to see before me the picture of that astounding scene!” That day they rescued approximately two hundred slaves.

escaped slaves 1862

Higginson, with his Boston Brahmin background, was an outsider looking into another culture. There is condescension on occasion but while he may refer to the former slaves as docile, he makes clear he knew they were not mentally deficient as so many others would report in northern publications. “I cannot conceive what people at the North mean by speaking of the negroes as a bestial or brutal race. … I learned to think that we abolitionists had underrated the suffering produced by slavery among the negroes, but had overrated the demoralization.”

Higginson viewed his troops as human beings who had been denied basic human privileges, privileges he had literally fought for long before the Civil War. Throughout the book he presents the former slaves as active participants in shaping their own destiny.”One half of military duty lies in obedience, the other half in self-respect,” Higginson writes. “A soldier without self-respect is useless.” Recognizing what he describes as the bequest of slavery, Higginson worked with his officers to “impress upon [the troops] they did not obey their officers because they were white, but because they were their officers, just as the Captain must obey me, and I the general; that we were all subject to military law, and protected by it in turn.”

Over time, more black regiments were formed. In 1864 the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry’s name was changed to the Thirty-Third United States Colored Troops. The men served until February 1866 when the troop was finally mustered out. “It is not my province to write their story, not to vindicate them … Yet this, at least, may be said. The operation on the South Atlantic coast, which long seemed a merely subordinate and incidental part of the great contest, proved to be one of the final pivots on which it turned. All now admit that the fate of the Confederacy was decided by Sherman’s march to the sea. Port Royal was the objective point to which he marched, and he found the Department of the South, when he reached it, held almost exclusively by colored troops. Next to the merit of those who made the march was that of those who held open the door. That service will always remain among the laurels of the black regiments.”

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

“… we who served with the black troops,” Higgins writes, “have this peculiar satisfaction, that, whatever dignity or sacredness the memories of the war may have to others, they have more to us. … We had touched upon the pivot of the war. Whether this vast and dusky mass should prove the weakness of the nation or its strength, must depend in great measure, we knew, upon our efforts. Till the blacks were armed, there was no guaranty of their freedom. It was their demeanor under arms that shamed the nation into recognizing them as men.”

Sources and Additional Reading

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_South_Carolina_Volunteers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Wentworth_Higginson

Army Life in a Black Regiment (Amazon)

https://www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org/thomas_wentworth_higginson

https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/06/rehearsal-for-reconstruction/

https://www.lowcountryafricana.com/project/history-of-the-33rd-united-states-colored-troops-usct/

http://www.drbronsontours.com/bronsonportroyalexperiment.html

https://www.sciway.net/afam/slavery/population.html

Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1862).Bombardment of Port Royal, S.C. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f9a8-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. (1861 – 1865).Two views. Dress parade of the First South Carolina Regiment (Colored), near Beaufort, S.C. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-c8e9-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Please note that the Library of Congress has an extensive collection of photographs available online from this period in U.S. history.

donald langosy: the poet’s painter

Posted in Books I Love, Inspiration, tagged art, books, creativity, Donald Langosy, ekphrasis, Eric Sigler, Inspiration, muse, painting, poetry, poetry books on December 11, 2017| 1 Comment »

One year ago it was my pleasure to share, in his own words and images, a glimpse into the life of painter Donald Langosy. Through his 14-page Story of My Art, that I condensed into roughly six blog posts, Mr. Langosy shared his amazing creative journey that involved the likes of Ezra Pound, William Blake, his wife Elizabeth and of course there is Shakespeare. His work is unique and quite inspiring as can be seen in the new book Donald Langosy: The Poet’s Painter. This book of 99 poems by Eric Sigler illustrated with full-color reproductions of the 99 paintings by Mr. Langosy that inspired the poet.

Available online from a variety of vendors as listed below. If I have one criticism, after having seen firsthand the scale of some of these paintings, it is that I wish the book was physically bigger. Meanwhile I hope there will be an art opening one day so that more people can view his work up close and meet both painter and poet!

https://eyewearpublishing.glopal.com/en-US/p-8574461128/donald-langosy-poets-painter.html