Previous Interludes

Portrait Eric Stenger, 1906, Museum Ludwig, Foto (c) Rheinisches Bildarchiv

At the end of one letter, Dr. Erich Stenger writes, “I am up to my neck in work again and often regret that we did not get together more while you were here. There would have been so much more to show and to discuss. The director of the Kodak Museum B. Newhall has announced his visit. And when will YOU be returning to Germany?” (excerpt from 1950 letter from Stenger to Joseph A. Horne)

Erich Stenger (1878-1957) was a noted photographic historian and collector. He trained as a chemist. He worked during the early days of photography when photography was viewed more as a science rather than art. In 1905, he would join the faculty of the Technische Hochschule in Berlin as an assistant instructor in the photographic department. In the early 1900s, he co-wrote papers on The Fundamental Principles of Three-Colour Photography, and Radiation Sensitiveness of Silver Bromide Gelatin for White, Green and Orange Light. By 1934, he was named to the chair of photography founded in 1864 by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, a post he would retain until his retirement as Professor Emeritus in 1945. He began building his photography collection as a student and would do so until the end of his days.

Portrait Franz Grainer, 1920er Jahre, Museum Ludwig, FH 2438, Foto: © Rheinisches Bildarchiv

His collection was diverse, from landscapes to portraits, to decorative framed items to caricatures about photography. Beaumont Newhall wrote that “At the time of World War II, his collection was said to be the largest in private hands anywhere in the world.”

Hermann Wilhelm Vogel: Dreifarbendruck nach Verfahren: Vogel-Ulrich.

Aufnahme nach Ölgemälde und natürlichen Schmetterlingen 1892

Museum Ludwig, FH 10248, Foto: © Rheinisches Bildarchiv

Beaumont Newhall (1908-1993), referred to in Stenger’s letter, was a pioneering historian and first curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Beaumont Newhall, Self Portrait, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1970.

Over his career, he would write five editions of the signature work, The History of Photography. In 1945-1946, the Roberts Commission would recommend him as a good candidate for the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archive unit. Paul J. Sachs described Newhall “as one of the best men for library work.”

Newhall’s name appeared on one of the last lists of qualified officer personnel that the Roberts Commission presented to the War Department, indicating that “the only alternative after this is enlisted men.” Newhall would not be assigned to the unit. After discharge, Newhall returned to the U.S., continuing his research, lecturing, and curating photography exhibits. In 1948, he became the first Curator of Photography at the Kodak Eastman House in Rochester, NY and would serve as its director from 1958-1971.

One of those enlisted men who would join the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archive unit was Joseph Anthony Horne. And as part of that unit, Horne would meet Dr. Erich Stenger and learn of his unique photographic collection. Exactly when and where Horne first met Stenger in postwar Germany is unclear but the friendship they developed, as indicated through correspondence about everything from photography to family, would endure for a decade. That friendship must have stemmed from a mutual love of photography. Horne had been a photographer with the Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information (FSA-OWI).

Horne’s MFA&A colleague Paul Vanderbilt, during an Investigation Trip to Interview German Authorities and Inspect Private Papers, reports meeting Stenger in September 1946:

Vanderbilt recommended:

Horne certainly met Stenger at a December 1946 meeting of photographers and photographic scientists “to discuss the present situation of the photographic trade and industry in Germany.” Mr. Horne had been invited to attend by the Berlin Press Photographers Guild. In his report following the meeting, he echoed Vanderbilt’s recommendations that Stenger be aided in reassembling his photographic collection, a collection spread across a divided postwar Germany.

Germany Occupation Zones 1946

It is unclear from available records how helpful Horne, Vanderbilt and the other Monuments Men were in helping Dr. Stenger rebuild his collection in a post-war, rapidly becoming Cold War, world. What is clear is that this unit of librarians, archivists and those dedicated to preserving and sharing knowledge, felt strongly about helping this gentleman as much as they could.

As the socio-political landscape of Europe changed, and with it the U.S. presence, Horne prepared to move on to other positions within the U.S. foreign services. Regardless, he and Stenger stayed in touch, corresponding about family and photography, and perhaps even their shared interest in stamp collecting. Horne would highlight opportunities for Stenger to exhibit photography, and Stenger provided updates on the health of his collection.

“The day after tomorrow I will be going to Switzerland, where I have been asked to come to deliver a few scientific lectures. I will be back home in mid-November. While in Switzerland, where I used to make annual purchases from merchants who knew what I was collecting, I will once again be on the look-out for my collection. Not having been back in eleven years, most of the merchants won’t remember me. Recently I was able to acquire some very special objects here in Germany; considering the awful destruction, I marvel that here and there something useful still pops up.” (excerpt from 1950 letter from Stenger to Joseph A. Horne)

Henry Traut, Porträt, München, Museum Ludwig,

1932, Foto: Rheinisches Bildarchiv

In 1955, Stenger’s diverse collection was purchased by the company Agfa, and today it complements a number of other collections as part of the Photographic Collection of the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. Stenger died in September 1957, and as Beaumont Newhall states in a later editorial, the world of photography lost a foremost historian and collector.

Sources and Additional Readings

The Photographic Collection of the Museum Ludwig

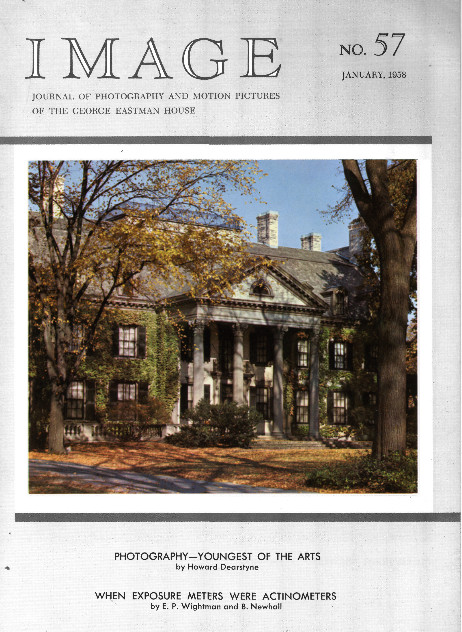

Image Magazine, 1958, incl. editorial on Dr. Erich Stenger

press page about the Stenger Collection

About Beaumont Newhall (International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum)

Beaumont Newhall (Scheinbaum & Russek LTD)

Oral History Interview Beaumont Newhall

More about Paul Vanderbilt

Source of historical military records

Read Full Post »